Filenews 14 February 2025

Five years after Britain left the European Union, the effects on the country's universities are being felt, confirming the initial fears of opponents of Brexit. According to research by Times Higher Education, the decline in European students is accompanied by an increase in Chinese and Indians, with the effects hitting both the economy and research.

While Nigel Farage, one of the pioneers of the Brexit movement, welcomed on January 31, 2020 the... With Europe's "The Final Countdown" as the soundtrack, describing Britain's official exit from the European Union as "the greatest moment in modern history for our great nation", the country's academic community recorded its concerns about a change that was expected to have overall negative effects on British universities.

The effects of Brexit probably took a back seat initially, as they were overshadowed by the Covid-19 pandemic. But today, five years after the Final Countdown, many experts are finding that the negative effects are starting to become apparent.

Anand Menon, Professor of European Politics and International Relations at King's College London and head of the UK in a Changing Europe thinktank, looking at the consequences of Brexit based on data from the Economic and Social Research Council, notes that, although universities themselves have not been particularly affected since leaving the EU, What has really been "damaged" is the image of the country with the corresponding negative impact on universities. More simply, Great Britain is now seen by many Europeans as a "less welcoming place", while many universities are making a huge effort to attract European students, as since August 2021 they have been forced to pay tuition fees as "international" students.

Changes in the composition of the student population

According to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (Hesa), European postgraduate students make up only 6% of the total in Great Britain for the 2022-23 academic year, compared to 15% in 2020-21 and 20% in 2018-19.

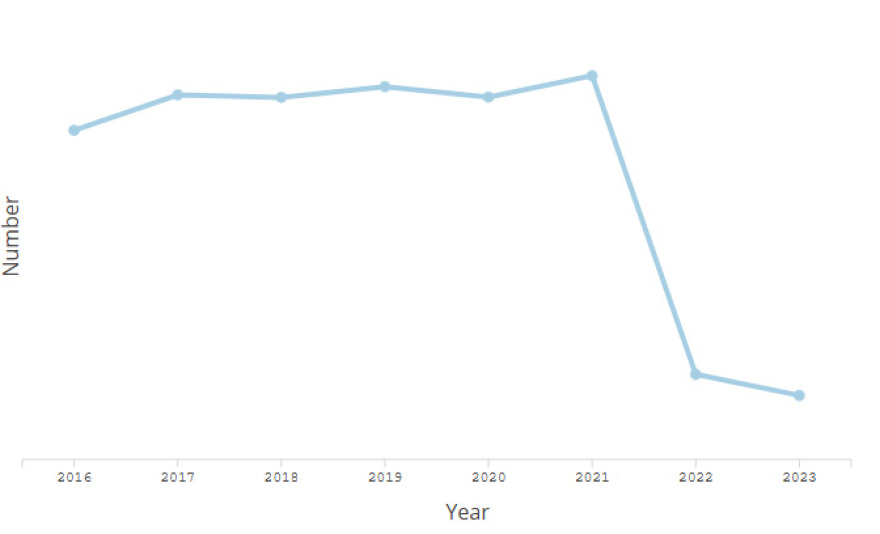

In the 2022-23 academic year, the total number of European students entering British universities at all levels was 28,905 – the lowest number of new entrants since 2008-09. Compared to the rest of the student population, in 2022-23 the number of students from China, India and Nigeria was ten times higher.

"From a HEI perspective, the most significant shift is in the cultural diversity of the student population, with the entry of young people from so many non-EU countries," says Vicky Lewis, academic advisor and expert in international strategy. "The constant refrain on the part of academics is that they 'miss' European students, who introduced a different 'look' to university auditoriums and contributed to the educational process. In addition, they develop more intense action outside the classroom, participating in social and group activities", she says, adding that "with Brexit and the decision to withdraw Great Britain from Erasmus+ student exchange programs, there was a corresponding decrease in the number of European students who participated in them, resulting in "narrowing horizons" of British students".

Although Erasmus+ has been replaced in Great Britain by the international Turing Scheme, which funds the participation of British students both in Europe and around the world, as of September 2021 it is proving not to be particularly successful. At the same time, it "carries" the disadvantage that it does not financially support foreign students to choose England as a destination.

According to recent research, it is proposed to reintroduce a pattern of youth mobility between the UK and Europe. However, the European Commission's proposals for European students to pay the same fees as native students would further damage universities' finances.

Scores in British universities are falling

Experts say the decline in the number of European students has also hurt universities' rankings, as they traditionally score higher. "European students are usually much more committed to their studies and typically receive high grades and quality assignments," says Martine Garland, professor of marketing at Aberystwyth Business School.

By "shrinking overnight" the market, Brexit in fact forced mainly those institutions established after 1992 to admit weaker students, in order to maintain the same number of students and, by extension, not to lose their financial viability, but to burden the academic staff accordingly. According to her, "these data, combined with visa restrictions and tuition revenues frozen for years due to rising inflation, create the 'perfect cocktail' for an economic crisis in the higher education sector."

Adding to the negative effects is the decision of the previous British government to ban international postgraduate students from bringing their dependent family members to the country, resulting in a dramatic drop in enrolments. The "inconsistency" observed is summarized in the shape of the formation of a model of higher education, which depends to a large extent on foreign students and then this is negated through the effort to reduce the number of immigrants – including foreign students. This leads with mathematical precision to an economic crisis, experts argue.

Top universities are "untouchable", the rest are "victims" of Brexit

The top universities may not be particularly affected by a decline in the number of their students, based on their prestige and reputation, but as the scale goes down, many universities have to fight to attract foreign students, who will come to balance the local student population.

Many of the international students in Great Britain today come from China and India, despite repeated calls for the recruitment of new students to be more diversity-oriented and include the parameter of different origins, in order to avoid unexpected geopolitical changes.

Reduced prospects for high-level academic staff

Ben Sheldon, professor of ecology at the University of Oxford, has already felt the impact of Brexit on recruitment: "One of the most obvious consequences is the enormous difficulty in attracting students from Europe as they face the problem of tuition fees tripling compared to pre-Brexit times. Many of these students could go on to become postdoctoral researchers and, subsequently, academic staff, so I think we are turning off the tap on an important pool of high-level academic staff."

Professor of physical chemistry at UCL, Peter Coveney, said there was a problem with hiring teaching and research staff in the absence of differentiation regarding their origins, while applications from Chinese researchers would gain ground. "It's a desperate situation... and we have, at the same time, a problem in relation to funding. In fact, there is a big drain of interest from Europeans to come to Great Britain," he said.

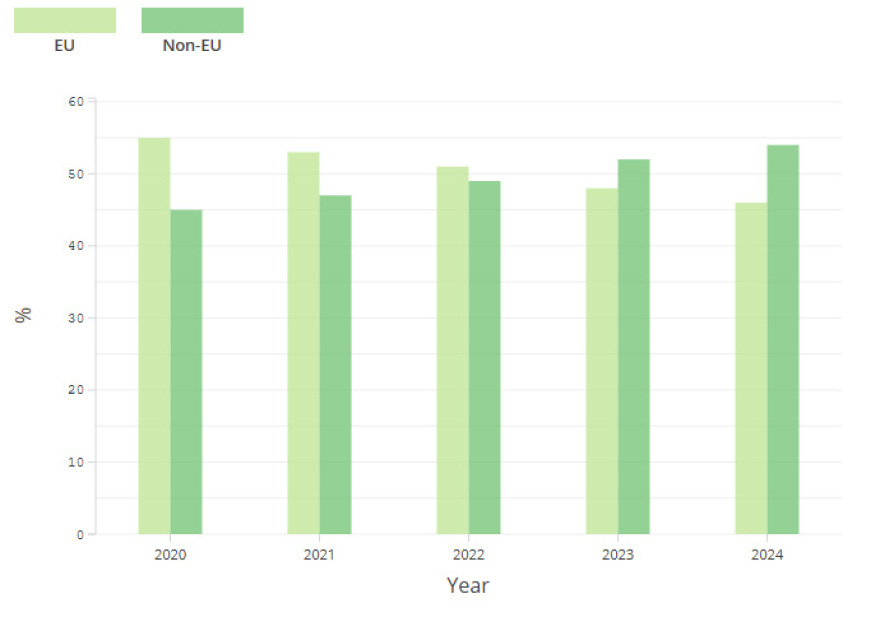

The composition of teaching staff in Britain's universities has changed since Brexit, statistics show. 15% of academics at British universities were European, up from 18% in 2018-19. In fact, they were replaced by colleagues from other countries around the world, with the total number of non-EU academics doubling in the last decade. Moreover, according to a recent study, since Great Britain's exit from the EU, the country has attracted lower-level faculty members.

The impact on the research landscape and scholarships

Another important parameter is the loss by Great Britain of its "share" of influence in Europe's research framework, Horizon Europe, since they are no longer able to co-shape the research landscape with their European colleagues.

The downward trend seems to have been taken by the British Institutions, with the existing teaching staff stating that they have fallen into a worse position, since they no longer belong to the "serious players", mainly in matters in the field of Hyperinformatics. "With fewer high-level Europeans, we are forced to turn to postdocs from China," explains one academic.

There were also fewer opportunities for Britons to receive substantial fellowships, awarded by the European Research Council, for "groundbreaking research". It is worth mentioning that in 2015, a year before the Brexit referendum, UK-based researchers had won the most fellowships at each of the three levels of researchers – 17% young researchers, 22% in the second tier and 25% in the third. These percentages fell to 8%, 14% and 16% respectively per category by 2023.

Top British universities also receive significantly less funding for research than in the past. Specifically, the 18 Foundations belonging to the Russell Group published figures confirming the above: in 2023-24 they received a total of £278 million in research grants and agreements with the European Commission when in 2022-23 they had received £339 million and in 2019-20, £405 million.

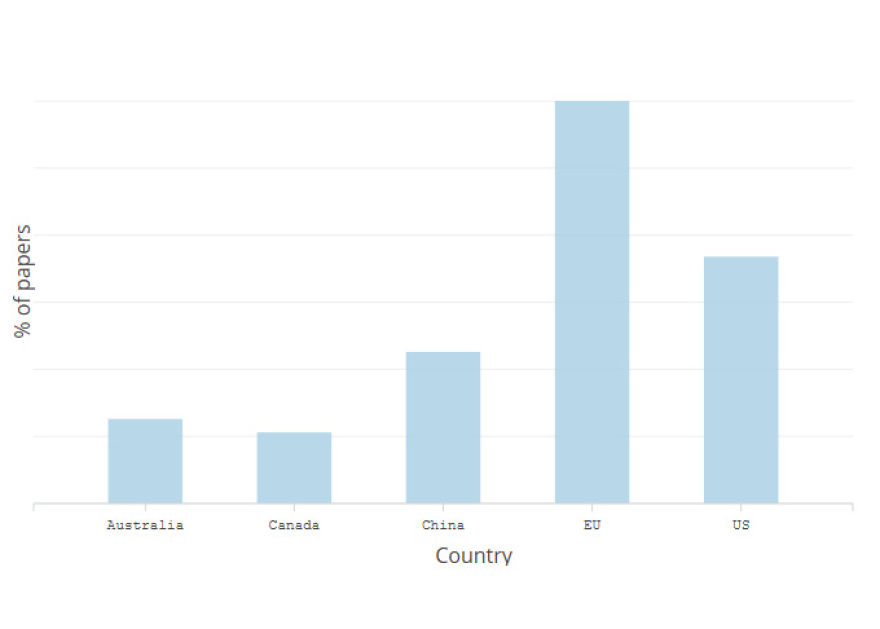

As far as research collaborations are concerned, however, there do not seem to have been much change in the UK. The proportion of scientific publications from Britain, in collaboration with at least one partner out of the EU27, has risen since 2016, with the proportion expected to reach 30% by the end of 2024 – the latest figures have yet to be published.

Although Britain has not reached the level of the US, it remains the second most fertile scientific partner for the 27 EU members, with an 8% presence in last year's publications. Great Britain's position in the international research ecosystem has undoubtedly become so entrenched that there have been no significant changes in scientific collaborations since Brexit.

In any case, any "obstacle" to international collaborations could have an impact on the success of research – "if you are not an active member of the global network, then you are not part of the discussion", say representatives of the British research community.

By Vasiliki Chrysostomidou protothema.gr