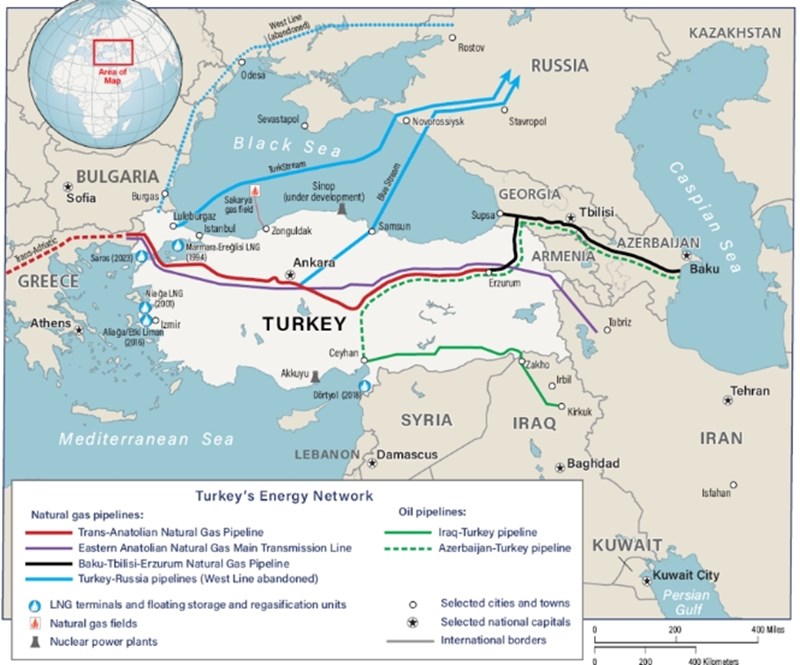

Turkey is located at the crossroads of Europe, Russia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East — a region with an excellent geopolitical position in the Eastern Hemisphere. As Europe and the U.S. seek to reduce their dependence on Russian energy corridors as well as Iranian oil and gas, Ankara is moving to establish itself as a key transit hub connecting Asia to Europe. With no significant reserves of its own, Turkey leverages its geographic location, including Russia/Black Sea, the Caucasus, Iraq, post-war Syria, and access to Europe. Tayyip Erdogan is trying to balance among his allies to expand his country's regional influence.

The collapse of the Assad regime in Syria by the Turkish-backed Hayat Tahrir al Sham, an offshoot of al-Qaeda and ISIS, the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, and escalating tensions between Iran, Israel and the United States have reshaped power dynamics in the region. With Russia and Iran weakened, Turkey is intervening, not only as a political-military actor, but also as a logistics hub. From the so far unsuccessful efforts to revive the Kurdistan oil pipeline to the exploration of routes from Azerbaijan through Armenia and Iraq's "Development Road" project, Ankara is promoting an ambitious project on three fronts — energy transit; diplomacy and military influence — to strengthen its geopolitical influence.

The Fall of Assad: A Historic Turning Point in Syria and the Middle East

During Syria's decade-long civil war, more than 600,000 people were killed, some 5.4 million displaced. became refugees and almost 7 million were displaced within borders. After decades of authoritarianism, the Assad regime fell in December 2024, and the geopolitical balance in the Middle East was upset. Assad had the support of Iran and Russia. With Moscow having exhausted its military forces in Ukraine and Iran's air defenses having been hit critically by Israel, these two regional powers have lost significant influence. Russia appears to have lost its only refueling station in the Mediterranean, while Iran has lost its closest Shiite ally.

Turkey, on the other hand, emerged as the main external power in post-war Syria. Ankara has backed many of the Syrian rebel groups and carried out military operations on its southern border to attack Kurdish fighters it considers a threat to its national security.

After Assad's defeat, Ankara rushed to sign deals with Syria's new transitional government, even though it has its roots in al-Qaeda. Although Turkey initially designated HTS (Hayat Tahrir al Sham) as a terrorist organization, as did the U.S. until Foreign Minister Marco Rubio revoked the designation in July 2025, Ankara supplied HTS with advanced weaponry, and offered it military and logistical support, strengthening the organization's dominance in northern Syria. from where he set out to finally overthrow Assad.

Turkey sees postwar Syria as an opportunity to earn billions from trade and reconstruction, as well as from extensive energy and defense projects. There are rumours that Turkey will build a military base in Syria to train and rebuild the capabilities of the Syrian army. This further increases Turkey's influence in Syria and may cause tensions with Israel, which Ankara regularly attacks in Turkish and international media. Finally, there is also hope that some of the millions of Syrian refugees hosted by Turkey will return home, as their presence abroad has caused internal tensions and a decline in Erdogan's popularity.

Turkey is making use of its strategic position

Turkey is conducting balancing exercises between NATO, Russia and Ukraine. It hosted the peace talks between Russia and Ukraine in May and July 2025. Turkey is in favour of Ukraine, providing military support and closing the Bosphorus Strait to Russian naval power, but without behaving anti-Russian. Ankara has not adopted sanctions against the Kremlin and maintains open diplomatic relations with both countries. Although its complex relations with Russia are an asset, according to Erdogan, Turkey's position as the sole mediator in this war makes it appear an unreliable partner in the eyes of other NATO member states.

Russia's traditional influence has also weakened in the Caucasus, and Ankara is filling that power vacuum as well. Although it has been a strong ally of Azerbaijan, the normalization of relations with Armenia is now on the table. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan made history as the first Armenian leader to make an official visit to Turkey after Armenia's independence. Ankara is even trying to play the role of mediator between its two neighbours over the peace treaty that will end the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh.

This mediation and normalization of relations could, in return, pave the way for a pipeline that would carry Azerbaijani gas to Europe via Armenia and Turkey, via the Zangezur Corridor, now known as the "Trump Corridor for Peace and Prosperity." This would break Armenia's isolation from key transit routes, reduce its dependence on Russia, and strengthen Turkey's position as a transit hub. Currently, the Southern Gas Corridor (including TANAP) already transports Azerbaijani gas via Georgia to Turkey and Europe, but bypasses Armenia. However, the Zangezur corridor would be a complementary route, which could strengthen Armenia's economy and regional transit role and offer Ankara greater strategic depth in the Caucasus.

Carnegie Endowment for International PeaceCarnegie Endowment for International Peace

Finally, Turkey submitted a proposal to Iraq to renew the agreement on the Kirkuk-Ceyhan oil pipeline, which has not been operational since 2023 due to political and economic differences. In 2023, a court ruled that Ankara must pay 1.5 billion euros. As compensation to Baghdad for illegal oil exports by the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq during the period 2014-2018. The dispute arose after Iraqi crude oil was loaded onto a tanker in the Turkish port of Ceyhan, on the orders of the Kurdistan Regional Government, which is a violation of the 1973 agreement between Turkey and Iraq on the pipeline.

While Baghdad seeks to centrally control oil exports, Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, is focused on achieving economic and political autonomy. Negotiations between Baghdad, Iraq's Kurdistan Regional Government and independent oil producers have failed to reach an agreement on the terms, further delaying the reactivation of the pipeline. However, Ankara now has bigger ambitions, such as the "Development Road" project, a major infrastructure corridor worth 17-20 billion euros. connecting the port of Basra in Iraq (in the Persian Gulf) with Turkey's border and away with Europe. It combines highways, railways, and plans for a pipeline and electricity transmission infrastructure. It could be an alternative to the Kirkuk-Ceyhan oil pipeline, which connects the Basra oil fields to Cheyhan, completely bypassing the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region in Iraq.

Important but "complicated" ally of the USA and NATO

Although Turkey is theoretically a U.S. ally and a member of NATO, its self-centered and contradictory policies toward Russia, Hamas, and Israel often create tensions with Washington. Turkey has never adopted the sanctions imposed by the West on Russia, has become one of the most important buyers of Russian crude and an increasingly important destination for Russian gas after the expiration of Gazprom's transit agreement with Ukraine. Ankara has also helped circumvent sanctions on the Russian side, taking advantage of the sanctions-free status of Gazprombank to funnel billions through U.S. banks to Turkey's state-owned Ziraat Bank, which then distributes the funds to Russian companies to finance Moscow's military operations.

Turkey's "complexity" in the context of its alliance with the United States is not unique in its history. Ankara has found itself in a similar confrontation with Saudi Arabia and Egypt as it backs the global Islamist Muslim Brotherhood movement, which has been banned in many Muslim countries. Turkey protested when Egypt's former defense minister and current president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi overthrew Mohamed Morsi of the Brotherhood in 2013, its relations with Cairo deteriorated, while the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018 brought tension to Riyadh. The different positions on Libya and the blockade of Qatar by Saudi Arabia "deepened" Ankara's rift with Cairo and Riyadh, frictions that had been simmering since the Arab Spring.

In particular, while the United States is Israel's strongest supporter, Erdogan is one of the most vocal critics of Jerusalem, providing shelter and financial support to Hamas terrorists, while at a UN assembly he likened Netanyahu to Hitler creating diplomatic tension. Although Erdogan and Netanyahu maintain good relations with Trump, the two are at odds over Gaza and Syria.

These tensions, combined with the balances Turkey wants to maintain with Russia and NATO, make its cooperation with the United States occasional, with the two countries agreeing on Ukraine and the Caucasus, but diverging in the Middle East. As Ankara pursues its own strategic course, often financed — and coordinated — by Qatar, where it has deployed about 4,000 troops, Washington is called upon to manage a "difficult" NATO member whose regional ambitions often undermine U.S. allies and strategic priorities.

As traditional energy routes through Russia have become politically unviable and Iran's intransigence is likely to bring further sanctions on its energy exports, Turkey is attempting to fill the gap. From Syria to the Caucasus, from Iraq to Armenia, Ankara's foreign policy is increasingly linked to pipelines, energy corridors, strategic bottlenecks and support for militant Islamist movements.

Energy transit is no longer just an aspect of its regional role, but complements the geopolitical puzzle of its strategy. As regional alliances shift and global demand for alternative routes to Russia and Iran grows, Ankara is betting that control of infrastructure will translate into long-term strategic influence and power multiplier.