Filenews 21 February 2025 - by Marc Champion

We need to redefine Donald Trump's approach to ending Russia's war in Ukraine. What he is negotiating is a reset – a "reset" – with Russia, making Kiev and its future the most valuable card in the hands of the US president, in a swap.

Viewed in this light, it should come as no surprise that Ukraine and Europe were absent from Tuesday's high-level meeting between Putin officials and the Trump administration, as it was about the relationship between America and Russia, not Ukraine. Nor by the otherwise shameful way Trump is now trying to stigmatize Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky as the obstacle to a deal.

It is also beginning to make more sense that the master of the "art of the deal" would begin — not end — his campaign with phone calls to President Vladimir Putin, and immediately cede much of its demands on Ukraine to Moscow before talks on the war even began. These concessions already range from a "no" vote to Ukraine's NATO membership or the return of its occupied territories, to calling for wartime elections to get rid of Zelensky — a first step in the Kremlin's demand for what it calls the "denazification" of Kiev.

This view explains the presence in Riyadh of Kirill Dmitriev, director of the Russian sovereign wealth fund, who is also Putin's man for energy investments. The former Goldman Sachs banker's message to reporters in the Saudi capital was that Trump knows how to solve problems, and the problem he needs to solve is that the U.S. lost $300 billion in Russian businesses because of the war.

As with Trump's demand that Ukraine hand over $500 billion in fictional rare earth assets and other real resources, it matters less whether that amount is accurate and more that it is large. Dmitriev said he sees U.S. companies returning to Russia as early as the second quarter of this year — even if some of them could struggle to regain market share. In other words: How much do we have to pay the U.S. to get what we want about Ukraine?

According to Yale School of Management's CELI list of companies in Russia, there were 457 U.S. companies operating at the start of Putin's full-scale invasion in February 2022. Of these, 23 are still operating normally, 100 – including companies such as Procter & Gamble – remain but have reduced their operations, and the rest have either suspended operations or withdrawn altogether. The latter category includes some big names such as Exxon Mobil, whose 30% stake in an oil drilling project in the Far East was seized by the Russian state in October 2022. Exxon valued the stake at about $4 billion, and no doubt Putin could, if he chose, return it.

So there's a lot to discuss, with lifting economic sanctions an important tool in Trump's hands. That, as Foreign Minister Marco Rubio said on Tuesday, is a concession the United States will not make until there is a final agreement. But here, too, the government's stance looks more like it would take in negotiating a restart with Russia than the terms of a deal on Ukraine. Otherwise, as Daniel Fried, a top former State Department official in both Republican and Democratic administrations, told Bloomberg News, the lifting of sanctions would be better kept as an incentive for Russia to observe an eventual ceasefire.

The results of Tuesday's meeting in Riyadh underscore that Ukraine is being seen as a pawn in broader talks rather than their main issue. Rubio said the two sides agreed to restore diplomatic and economic ties and form negotiating teams to start discussing Ukraine in that order. He stressed the "incredible opportunities that exist for cooperation with the Russians, geopolitically on issues of common interest and frankly, economically" that ending the war would create.

Rubio was certainly not referring to a jackpot for the Ukrainians. While in Riyadh, Kiev was under pressure from the U.S. to accept Trump's demand that he sign off on 50 percent of all revenues from the country's mineral resources, ports and other infrastructure in perpetuity, as compensation for U.S. aid to Ukraine, and offered nothing in return. These are terms that victors impose on defeated enemies as war reparations and were undoubtedly designed to be rejected. And that now sets the stage for Trump to portray Ukraine and Zelensky — whom he outrageously now calls a dictator — as the problem.

If you don't believe that stronger countries should have the right to invade smaller ones, destroy cities, and slaughter and torture civilians in the process, then Trump reached a new nadir of immorality at his Mar-a-Lago press conference on Tuesday. Not only did he insist on mocking Zelensky's declining support in opinion polls after three years of conflict, calling on Kiev to hold elections, but he also blamed him for starting the war.

It helps to remember that — as I wrote after Vice President J.D. Vance's fierce criticism of Europe in Munich last week — Russia is by no means the enemy in the eyes of Trump or other like-minded ultranationalist political parties throughout the democratic West. Putin's Russia is for them more a comrade in the fight against the liberalism – domestic or international – that unites them all. Ukraine, meanwhile, has heralded itself as a struggle for the liberal world order.

If all of this makes Trump's actions easier to understand, that doesn't change the shameful and false nature of the narratives he's embraced by the Kremlin. Ukraine did not start this war – Putin did not invade because he was threatened by NATO aggression, as I have argued in detail here – and elections under conditions of war and martial law are not a democratic necessity for Ukraine, but would rather be unconstitutional, destabilizing, and logistically unlikely. Although Zelensky's approval ratings have certainly fallen from their highs at the start of the war, Trump's claim of 4% is simply unfounded. At 57 percent this month, the Ukrainian president's ratings are still better than those of many heads of state, including Trump (about 46 percent).

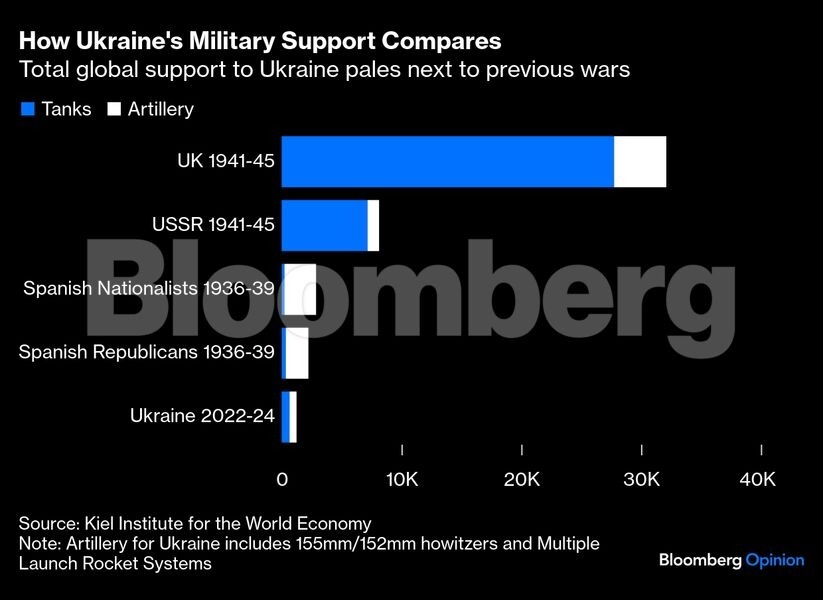

As for the US president's claim that America needs $500 billion in compensation for its support, again, the argument is based on pure misinformation. The U.S. has not given Ukraine $350 billion, Trump wrote on social media site Truth Social on Wednesday. On paper, it has given half of that, and in real, distributed resources, just 114 billion euros ($119 billion) by the end of 2024, according to Germany's Kiel Institute, which tracks all support for Ukraine in detail. Of this amount, 64 billion euros took the form of military support, the vast majority of which either came from warehouses or was paid to American arms manufacturers.

Nor has the U.S. shouldered a particularly heavy burden relative to other allies of Ukraine, as Trump and his aides never tire of saying, let alone $200 billion more than Europe, as he claimed in a blog post. The U.S. has consistently spent less than Europe, and as a percentage of gross domestic product ranks just 15th among Ukraine's top 20 donors in wartime.

Trump is nonetheless right on this issue: The U.S. remains the critical player for Kiev, both because of the weapons classes it provides and because of its deterrent capability as the world's largest military and nuclear power.

It is possible that Trump will surprise everyone by striking a fair deal on Ukraine as part of his "relaunch." Nothing, however, that the leader of the free world has said or done so far inspires confidence that this will happen. Most likely, and tragic for the people of Ukraine as well as for the future stability of Europe, we are seeing an agreement unfold to their detriment by two extremely cynical leaders, who both see the weak as targets to be exploited and the strong as the only ones worth negotiating with.

Performance – Editing: Lydia Roumpopoulou