Filenews 10 February 2025 - by Robert Burgess

This week we learned that the reason it's hard to determine the Trump administration's trade policy goal is because there isn't really a clear goal. Is it aimed at reducing the US trade deficit? Is it about raising revenue to fund the extension of the 2017 Tax Cuts Act (TCJA) that expires later this year? Is this about gaining diplomatic power in other negotiations, such as border security?

Whatever the goal of this policy, it is unlikely to benefit either U.S. debt and deficits or the bond market.

Here's what President Donald Trump wrote in a social media post as he prepared to impose 25 percent tariffs on goods entering the U.S. from Mexico and Canada at midnight last Tuesday: "MANUFACTURE YOUR PRODUCT IN THE U.S. AND THERE ARE NO TARIFFS! Why would the United States lose TRILLIONS OF DOLLARS BY SUBSIDIZING OTHER COUNTRIES..." (Trump loves to use capital letters in his social media posts.)

Thus, it is clear that the use of tariffs is intended to correct any perceived U.S. trade imbalance with Mexico and Canada, its two largest trading partners. It makes sense. But Kevin Hassett, director of the White House National Economic Council, said no, it's not that. "This is not a trade war, but a war on drugs," he told CNBC. Maybe he's right? Mexico and Canada made some symbolic security concessions on their U.S. border on Monday, and Trump immediately suspended tariffs. The debate on tariffs as a source of revenue was barely mentioned.

There are two conclusions here. The first is that White House trade advisers certainly understand the contradictory nature of Trump's speech on tariffs and should talk to him about it. Trump has said such charges on foreign goods — paid for by U.S. citizens — would raise the funds needed to fund the TCJA extension, which the Congressional Budget Office estimates will cost $4.6 trillion over the next decade.

The other side of the coin is that tariffs make imported goods more expensive. Amid Monday's chaos, food wholesaler Associated Wholesale Grocers sent a warning to its 1,100 U.S. retailers to prepare to pay an additional 25 percent on goods from Mexico and Canada. It is also estimated that the average price of a car could skyrocket by about $3,000. As U.S. consumers complain about high food and other commodity prices due to elevated inflation resulting from the pandemic, this will give them an even greater incentive to cut back or look for cheaper alternatives (assuming price increases are not mitigated by currency adjustments, such as a stronger dollar and a weakening of the currencies of the targeted countries).

If U.S. consumers curb their spending, the tariffs won't generate the revenue Trump wants to fund a TCJA expansion. The result will be more debt and larger budget deficits at a time when U.S. borrowing already exceeds $36 trillion. dollars and government spending exceeds revenue by $1.8 trillion. dollars per year, or nearly 6.4% of gross domestic product. David Kelly, chief strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, in a recent note to clients put it this way:

Based on data through November, total U.S. imports of goods last year were about $3.3 trillion, which indicates an initial estimate of $330 billion. Dol. in annual revenues from an additional 10% universal duty on all imported goods. However, this amount would be significantly reduced to (1) account for reductions in import volumes due to higher prices, (2) the negative impact on GDP of retaliatory duties on exports, and (3) the possibility that duties could increase inflation and thus interest rates. Moreover, if the federal government tried to compensate exporters for the effects of retaliation, as happened in the first Trump administration, net fiscal savings would be further reduced.

If that's not enough to revolutionize the bond market, then consider that Trump's bullying of our closest trading partners and allies has certainly made countries around the world think about how to move away from the U.S. should they become the next target of tariffs — further shrinking Trump's expected tariff revenues. Canada is already looking for ways to decouple its oil operations from the U.S. and send more crude to Asia, according to Bloomberg News. And the European Union, which may be Trump's next tariff target, struck a deal with four South American countries in December to create one of the world's largest trading blocs.

Add to that mix the fact that U.S. exporters will also look for ways to avoid tariffs — as they did in Trump's first term. Trump's "threats and executive orders so far suggest that the emphasis right now is more on bargaining power," Bloomberg Economics wrote in a report Tuesday. "This approach is less suited to increasing fiscal revenues, as it allows imports to be directed away from tariff routes, eroding any extra revenue from rising rates."

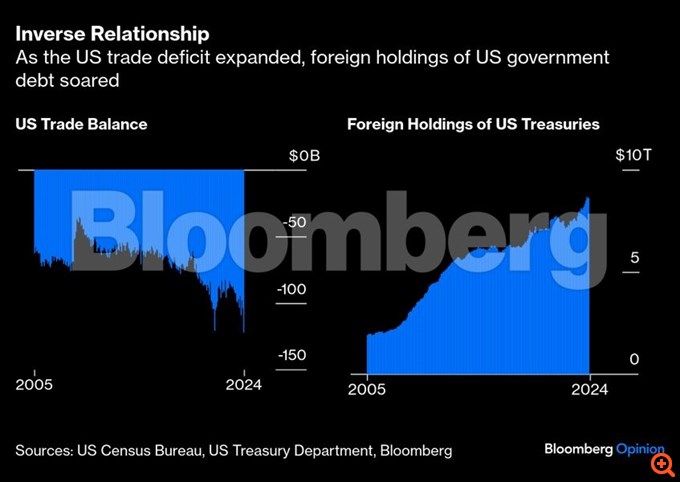

But few seem to talk about the fact that trade plays a key role in allowing the U.S. to run so much debt and large budget deficits. Trump's posts show that he equates U.S. trade deficits with support for other economies. However, the opposite is true. As Nobel laureate Paul Krugman has described in Substack, America buys goods and services at low prices that cannot be replicated in the US, and, in return, our trading partners receive an informal commitment (IOU) in the form of US Treasury securities. So it is actually America's trading partners that provide a subsidy through cheap imports and lower borrowing costs.

"Ultimately, Trump's tariffs are aimed at generating revenue at the risk of disrupting global capital flows necessary to finance the U.S. economy," TS Lombard's chief U.S. economist Steven Blitz wrote in a Feb. 4 note. "The current stable system of global capital flows running parallel to flows of goods may still be called into question if Trump's tariffs disrupt the regular flow of goods."

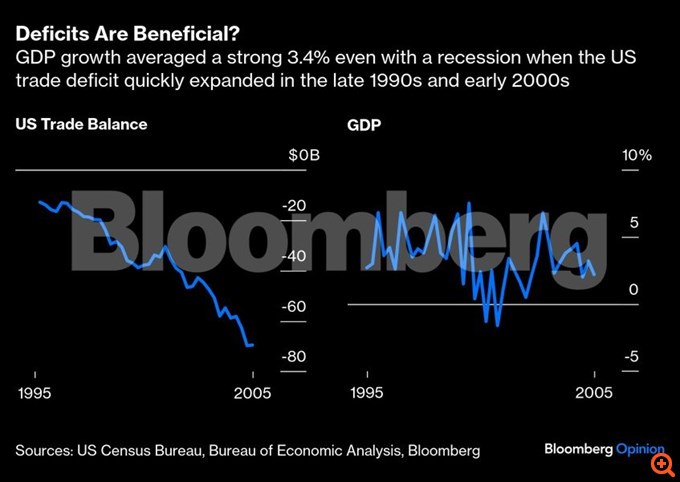

Or as Krugman explains, maintaining trade surpluses and attracting huge amounts of foreign capital is numerically impossible, as a country's trade balance plus net capital inflows generally always equals zero. That's why it's called the balance of payments – it's always in balance. Moreover, as Krugman notes, there is no evidence that a trade deficit hurts economic growth. He points to the period between the mid-1990s and about 2005, when the trade deficit ballooned and yet GDP averaged 3.4 percent, even after the recession that followed the bursting of the dot-com bubble.

Achieving a trade surplus may sound attractive and indicate economic success, but this can be misleading given the balance of payments equation. So when countries go from a trade deficit to a trade surplus, it can often be due to bad reasons. As Krugman has noted, when some southern European countries found themselves in crisis just twelve years ago, they went from trade deficit to surplus. But this happened not because they suddenly began to export more than they imported, but because the inflow of capital stopped, forcing a sharp decline in imports.

The reality is that the U.S. relies on foreign money to finance its mounting debt and inflated budget deficit. Of course, both need to be addressed, but entering trade wars is not the answer. Presenting trade as "good" or "bad," depending on whether America runs a surplus or deficit with its allies, risks turning an increasingly dangerous fiscal situation into a real crisis.

Performance – Editing: Lydia Roumpopoulou