Cyprus Mail 19 January 2025 - by Rebekah Gregoriades

|

| Killis is a small donkey – or man – from the ancient Greek it’s killos or killis. In modern Greek it’s gaidouraki |

For anyone learning Greek in Cyprus, the struggle is real.

While mainland modern Greek is taught as a second language to foreigners living on the island and can be used outside the classroom, it does not help when it comes to actually comprehending the Cypriots. Many are left baffled.

The problem is that Cypriot is a dialect which Cypriots speak amongst themselves, while they use modern Greek in schools and all official dealings.

So, why did the Cypriot dialect deviate so much from modern, mainland Greek?

The answer is it didn’t.

Modern Greek evolved from ancient Greek, while in Cyprus the exact same process has been much slower, gifting us words and phrases that have survived since the times of the Achaeans and through a parade of conquerors spanning centuries.

And although what is spoken today in Cyprus is very different, the Greek that Plato and Alexander the Great spoke over 2,000 years ago probably sounded very similar to the Cypriot dialect.

Historians over the years have said the Cypriot dialect is perhaps the only truly Greek dialect still alive today.

Some scholars support Cypriot Greek is not an evolution of ancient Arcadocypriot Greek but derives from Byzantine Medieval Greek, as Cyprus had been cut off from Greece in the 7th to 10th centuries due to Arab attacks, with a brief pause when it was reintegrated in the Byzantine Empire in 962, only to fall to the Crusaders in 1191.

However, Greek linguist Georgios Babiniotis has said that the Cypriot dialect has salvaged many elements from ancient Greek.

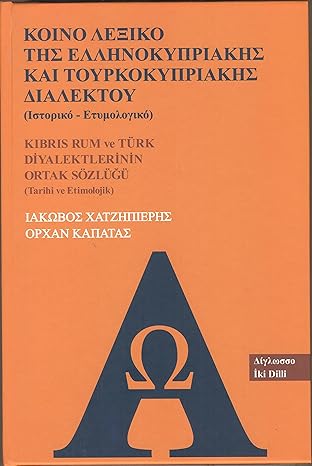

Co-author with Orhan Kapatas of the Joint Dictionary of Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot Dialect Iakovos Hadjipieris echoed this opinion, telling the Cyprus Mail that modern Greek evolved from ancient Greek, passing through various stages before emerging in its current form.

“The Cypriot dialect belongs to the southeastern” varieties of Greek, according to Babiniotis, who says Cypriots pronounce double consonants, “a very important characteristic of ancient Greek”.

Another characteristic he points out is the ending consonant ‘n’, which is not used in modern Greek but is widely used in Cyprus. “This ensures a euphony salvaged from ancient Greek,” Babiniotis explains.

Vowels in Greek may seem obsolete, however in ancient Greece the different spelling of vowels – for example the sound ‘i’ can be written in five different ways – lends a short, medium, long, sharp or heavy vocalisation to syllables, making ancient Greek a rather musical language.

One of the easiest ways to experience this is to watch Greek tragedies played in ancient Greek, as many productions in recent decades have made a point of staying true to the original pronunciation.

The structure of sentences is also different in ancient Greek, yet another characteristic still alive in Cyprus.

Words labelled as chorkatika or ‘village gab’ have their roots in ancient Greek, as does the grammar.

Walking through Cyprus’ scenic villages, most of what you hear might actually be ancient Greek.

Cypriot Greek “fills your mouth”, as the locals say, while mainland Greek is phonetically ‘crisp’.

Words themselves are a telltale of the dialect’s ancient roots.

For example, salt is alati in Greece and alas in Cyprus or als in ancient Greek.

Vortakos is a frog or toad in Cyprus, which has survived since ancient times – the word, not the frog – while in modern Greek it is vatrachos.

Killis is a small donkey – or man – from the ancient Greek it’s killos or killis. In modern Greek it’s gaidouraki.

Lalo means I say and is the same in ancient Greek.

The list is endless.

As for the structure of sentences, Cypriot follows the ancient grammar, while modern Greek differs.

For example, Eiden o vortakos ton killin tzai lalei tou en omorfos. Note the final ‘n’ in this Cypriot sentence.

To understand the difference, here it is in English:

Greek structure: The frog saw the small donkey and told it that it’s handsome.

Cypriot structure: It saw – the frog – the little donkey and to him it said he’s handsome.

To make things even more complicated, the Cypriot dialect presents differences across the island, with Paphians speaking a heavier dialect and those in the mountains talking faster.

Centuries of being attacked and conquered – with the latest being British colonial rule, from which Cyprus gained its independence in 1960 – meant that the Greek spoken in Cyprus has been seasoned with many other influences.

Many words heard in conversations among Greek Cypriots are of Turkish origin, while others are borrowed from English, Latin, Italian, French and Arabic.

So, apart from living in a linguistic time capsule, you might also say you are experiencing a kaleidoscope of regional languages, all added to ancient Greek and forming the Cypriot dialect you can appreciate today.

You better be quick, though, as the younger generation – powered by the internet – appears to be slowly leaving the heart of the dialect behind and incorporating an international approach to communication on a background of modern Greek.