Filenews 18 September 2023 - by David Fickling

In the new Cold War emerging between authoritarian states and democracies, oil seems to be the most powerful weapon.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman were celebrating last week their recent production cuts, which have led to a 23% rise in the price of crude since late June. More expensive oil means more money for Moscow's war machine and Riyadh's manufacturing boom, but also higher gasoline prices for U.S. consumers. Looking for an opportunity to highlight the importance of the yuan, China has meanwhile moved almost all imports of Russian crude oil to its own currency and has pressured Riyadh to do the same.

The battle lines have been drawn and U.S. President Joe Biden's climate-conscious administration is threatened with a mortal blow by an alliance of autocracies painted oil black.

"Chemical weapon"

Not so fast. One of the dangers of chemical weapons is that they can blow up on your side, and it's no different when the "chemical weapon" is a hydrocarbon molecule. Those who believe that an oil price war can act as a smart bomb targeting open societies and sparing dictators may be surprised by the end result.

That's because China — the largest source of additional oil demand in recent decades, accounting for about three-quarters of marginal growth in 2023 — is at a critical moment in its energy transition. Its gasoline demand will peak this year, according to China Petroleum & Chemical, the huge state-controlled refinery known as Sinopec. Road fuels in their entirety will follow next year, predicts BloombergNEF.

Every dollar Russia and Saudi Arabia now add to the price of oil will lead to a faster fall in long-term demand from their most important market, as well as from the country that will take over crude consumption: India. Climate activists should thank Moscow and Riyadh. The wrong fuss of exporters will do as much to reduce the world's carbon footprint as a library full of serious ESG reports.

There is a simple rule of thumb for understanding the short-term economic effects of oil supply shocks (the situation where producers reduce their production below consumer demand levels, as we see now): exporters get richer and importers get poorer. This was the case with the Arab oil embargo in 1973 and the Iranian revolution of 1979.

The China Factor

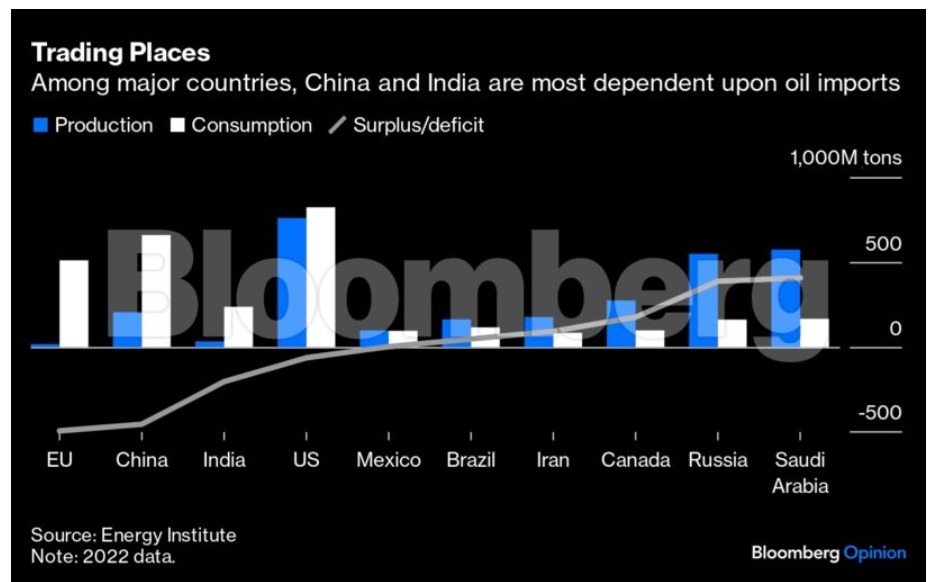

China overtook the U.S. as the world's largest oil importer in 2017. Domestic drilling now covers only about 30% of its needs, levels not much better than Europe's 22%. India, which both the democratic and authoritarian blocs want to attract, is the second-largest net importer and can only meet about 14 percent of its needs at home. The US, on the other hand, has been a net oil exporter for three years in a row.

Geological destiny means that strategic and climate considerations do not always work as expected. The U.S.is struggling to reduce oil demand because it is the world's largest producer, which risks dampening its leaders' decarbonization ambitions. Meanwhile, China — whose coal-fired economy accounts for a third of global emissions — has been remarkably effective at curbing oil demand because rising crude imports are hurting its energy security, as well as its environment.

For China, this is a particularly bad time to slash growth. Its real estate sector, which makes up about 30% of the economy, has been in a recession for two years that is driving prices down by double-digit rates. Government debt is estimated at $23 trillion, about double the level of gross domestic product seen in the US on the eve of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Attempts to stimulate the economy seem to be only small setbacks. Industrial profits are running at their lowest level since the 19 Covid-2020 pandemic – something unlikely to be helped by higher diesel and petrochemical prices, key cost drivers for many businesses.

Meanwhile, electric vehicle sales are booming. Seven of the 10 best-selling cars in July were cable-powered, while electric vehicles posted a 38% market share in August. Higher gasoline prices will encourage more drivers to move away from crude.

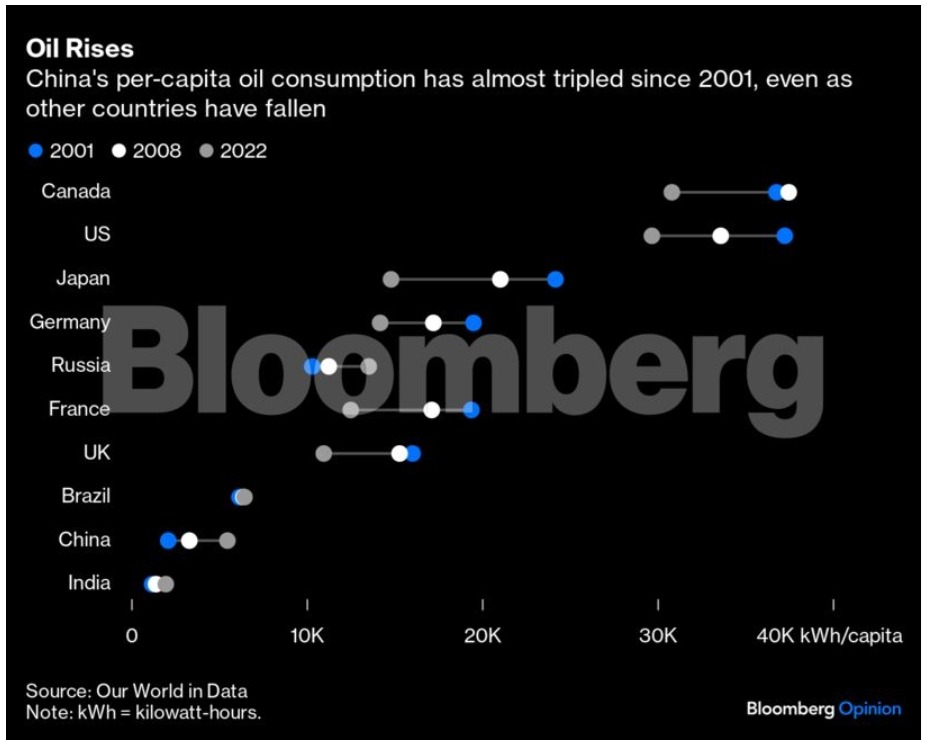

China has some strategic advantages over the US. Oil continues to be a smaller part of energy demand than in developed countries, so price gains weigh less heavily on economic activity. That's changing though — on a per capita basis, China's consumption has nearly tripled since it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, while many advanced economies have seen the same index fall by a third or more. It may also buy Russian and Iranian crude at a discount, although prices will continue to rise by international benchmarks.

It also has a stock to rely on. While Washington's Strategic Petroleum Reserve is running at its lowest levels since 1983, following volume releases by the Biden administration to stabilize the market in the wake of the war in Ukraine, China's oil reserves (whose actual volume is a closely guarded state secret) appear to be overflowing above 1 billion barrels. about three times the size of U.S. reserves.

This is not a comfort factor for exporters. If Beijing responds to higher prices by releasing barrels from its reserves, the effect will be to reduce import demand and lower global prices. This will dissipate the impact of Moscow and Riyadh's attempt to raise the price of crude.