Cyprus Mail 21 April 2021

|

| The Australian government has calculated that its marine industries will contribute around $100 billion each year to the economy by 2025 |

The world over, governments are viewing the ocean as a new economic frontier

By Maria Hadjimichael

A consequence of the economic crisis and the realisation of the finite nature of materials on land has prompted increased attention on the economic potential of the ocean.

Across the globe, the ocean is seen as a new ‘economic frontier’, a space which can be exploited to facilitate the restart of economies across the globe.

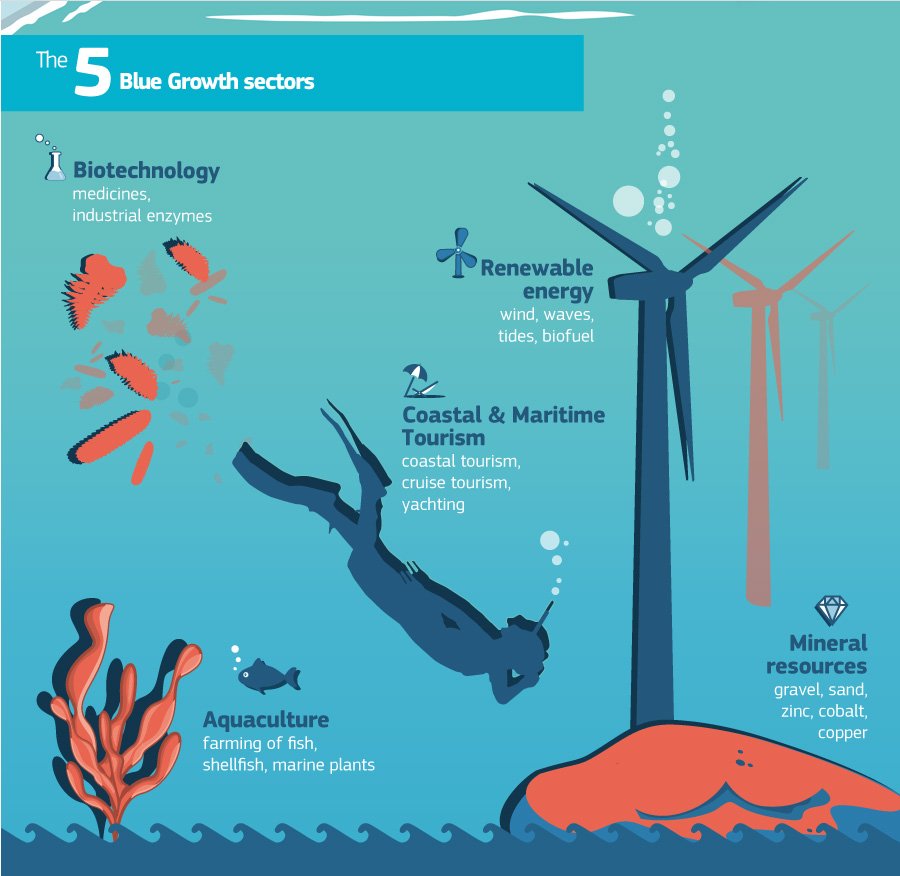

The ‘blue economy’ has taken different forms and names. For the European Union, it is termed ‘Blue Growth’ and described as “the long-term strategy to support sustainable growth in the marine and maritime sectors as a whole” whilst the “seas and oceans are (understood as) drivers for the European economy, with great potential for innovation and growth.” The Blue Growth strategy has identified marine aquaculture, coastal (and marine) tourism, marine biotechnology, ocean energy, and seabed mining as the sectors with the highest potential for jobs and growth.

In a similar vein, the Australian government has calculated that its marine industries will contribute around $100 billion each year to the economy by 2025. The marine economy is projected to grow three times faster than Australia’s gross domestic product over the next decade. In Africa, the UN Economic Commission for Africa developed a ’policy handbook’ in 2016, which described maritime development as “the new frontier of African Renaissance”, whilst the ‘Asia and the Pacific’s Blue Growth Initiative’ focuses on the sustainable use of fisheries and sustainable growth of regional aquaculture linking it with food security issues and poverty, an increasing regional and world demand for fish, and the need for the region’s economic development.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the UN has also put forward its own blue growth initiative linking it with a need for growth particularly in the fisheries and aquaculture sectors, in the framework of the achievement of relevant Sustainable Development Goal 14: ‘Life Under Water’. The World Bank has also picked up the term and defined it as “the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods and jobs, and ocean ecosystem health”.

In general, untapping the hidden wealth locked in the oceans has become a goal for many countries. As I understand it, this can be quite an exciting prospect for a significant portion of society as this would mean that (at least in) the global north, economies can find space and materials to grow, and thus we can continue the pretend game that they our lifestyles are sustainable.

The Republic of Cyprus, too, is slowly but steadily upping its game towards incorporating the blue economy in its wider plans for the economy. In March, the shipping deputy ministry of Cyprus initiated a new campaign with the slogan “SEA… YOUR HORIZON” with the aim to promote Maritime, Blue Studies and professions in secondary schools. In a short clip shared on social media to promote the campaign, young Cypriots describe the sea as a space which “exudes an air of optimism, confidence for the future” and state that they are ready to “embrace its prospects”. At some point, one of the students smiles and says, ‘our horizon, the blue hope’.

In essence, the shipping deputy ministry is moving along the lines of other countries, trying to engage with and exploit the new – and the not so new – economic potential of ocean space. Environmental impacts are covered by the vague and over-stressed term of ‘sustainability’, whilst social impacts take on the one-dimensional form of new employment opportunities.

Though some environmental Non-governmental Organisations have come forward to challenge the unquestioned promotion of the blue economy bringing up the issue of ‘limits to blue growth’, there has been generally little reaction. This has to do with the fact that our societies have an entrenched conviction of what has been termed as a growth-oriented imaginary, meaning that the growth of the economy is understood as an essential requirement of all political and policy decisions.

There is nevertheless increasing research into the ways blue growth imperative conflicts with the necessity to protect the ocean commons for future generations, and highlights the consequences it has on coastal and marine communities as well as marine biodiversity.

Over 70 years ago, Rachel Carson, the famous author of the book ‘Silent Spring’ published her book ‘The Sea Around Us’ (1951) which manifested, on one hand, the history of the ocean through science and poetry, and on the other, the inauguration of a nervous discussion over the future of the ocean. In her book, Carson probes a subject which today resonates as loudly as ever:

Over 70 years ago, Rachel Carson, the famous author of the book ‘Silent Spring’ published her book ‘The Sea Around Us’ (1951) which manifested, on one hand, the history of the ocean through science and poetry, and on the other, the inauguration of a nervous discussion over the future of the ocean. In her book, Carson probes a subject which today resonates as loudly as ever:

“It is a curious situation that the sea, from which life first arose should now be threatened by the activities of one form of that life. But the sea, though changed in a sinister way, will continue to exist; the threat is rather to life itself.”

Impacts of human activities at sea (such as over-fishing, oil-spills, coral bleaching etc) often enter centre stage causing a shock, either following high profile documentaries such as David Attenborough’s ‘Blue Planet’ or following human-made marine disasters. However, the parallel discussions over its potential for growth and jobs do not cross each other.

Is it the expansion of the economy that is required for a better societal and environmental planetary well-being or is it about time we started discussing the different ways in which our societies and economies can be structured putting the environment and the human well-being first?

Before we rule the oceans by extracting all that is economically important for today’s neoliberal market, it might be important to reflect upon the importance of ensuring that the ocean commons are left as a heritage for the future generations.

Maria Hadjimichael holds a PhD in marine governance. The article is based on ideas analysed and discussed in two published scientific papers ‘A call for a blue degrowth: unravelling the European Union’s fisheries and maritime policies’ and ‘Blue degrowth and the politics of the sea: rethinking the blue economy’.

The public can give their input on Cyprus’ national strategy here: www.cyshippingstrategy.com