Filenews 3 November 2025 - by Marc Champion

Who will disarm Hamas? And who will convince Israel to withdraw from the 53% of the Gaza Strip it still occupies? These remain the key questions plaguing Donald Trump's peace plan – and they need answers.

It is clear that neither side believes that the war is over, and we must acknowledge that U.S. officials, who rack up air miles with their travels, are trying to pressure both sides that Trump's truce has not already collapsed. Israel has accused Hamas of delaying the return of dead hostages and attacking its soldiers, retaliating with heavy fire. This cycle of violence has killed more than 100 people so far this week, according to Gaza's Hamas-run health authority.

Egypt – which is emerging as the region's leading power for Gaza – has also taken action. It sent machinery and personnel to the Lane to dig up the rubble and find the bodies of the missing hostages, in an attempt to prevent an uncontrolled escalation. He is also planning a conference on the reconstruction of Gaza in November.

But that's the easy part. Trump's plan was deliberately vague as to the details of how peace would be shaped after the ceasefire, and the complex diplomacy that will be needed to define those details has only just begun. What's worrying is that the road to a much more violent outcome is already much easier because both Hamas and Israel's settler movement are seeing ways to use the ceasefire to advance their messianic goals.

Without the presence of the international stabilization force that had to be deployed "immediately" under the terms of Trump's agreement, Hamas has not disarmed itself as it should. Instead, it has regained control of 47% of Gaza from which the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) has withdrawn. This is probably inevitable as long as there is a security vacuum and the IDF remains in full combat readiness directly opposite the so-called yellow line of the agreement. But when Hamas met with various other Palestinian factions in Cairo on October 23-24 to negotiate a common position on post-war governance, its representatives again did not agree on disarmament.

Hamas also said that while it would withdraw to give way to a government of technocrats from Gaza, it would not hand over control to the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank. It is run by Hamas' fierce political rival, Fatah, which has even refused to attend the meeting in Egypt. This is a political and potentially resolvable issue, but Hamas has also said it would only accept an international stabilization force if its mission was limited to ensuring that the Yellow Line is upheld and that peace is monitored – in other words, not the heavily armed force it would need to impose control, blow up tunnels and strip Hamas of its weapons.

Not surprisingly, the U.S. is having trouble finding candidates for this role. What reward would there be, after all, for getting between Hamas and the Israeli army, when every now and then your soldiers may face an attack that will trigger a new series of bombardments by the Israeli army across the Gaza Strip? Missiles do not distinguish peacekeepers, nor civilians. "What is the order?" asked King Abdullah II of Jordan in an interview with the BBC on October 27. "If it's about imposing peace, no one will want to take it on."

Meanwhile, in Israel, right-wing parties in Benjamin Netanyahu's governing coalition angered the U.S. by pushing through parliament legislation to annex the West Bank, a move that will likely undermine Trump's plan for Gaza. The same parties run the ministries responsible for both the security and finances of the West Bank. They have long insisted that Gaza should never be returned to Palestinian control and that settlement should instead begin. In a conflict where refugee camps are 77 years old and the West Bank has been under temporary status since its occupation by Jordan in the 1967 war, it is all too easy to see how Trump's yellow line could end up being permanent.

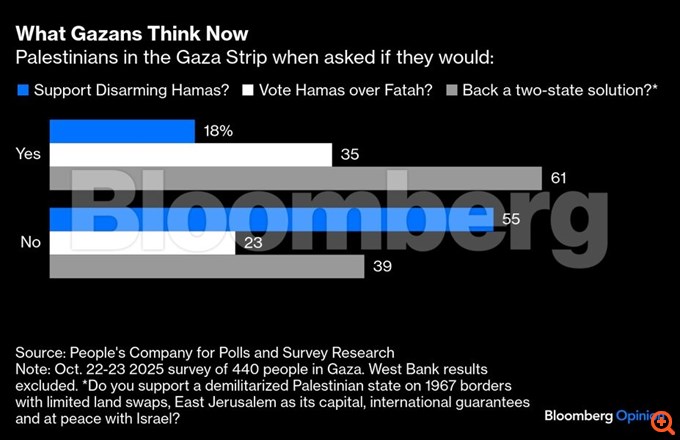

Netanyahu has said he will not allow the annexation bill to become law. However, it will not withdraw the Israeli army from Gaza unless Hamas is demilitarized, while Hamas will not be demilitarized as long as the Israeli army remains there, if that happens. What makes this cycle even more difficult to close is that both positions enjoy the popular support of their respective communities. According to the latest edition of a periodic poll of Palestinian public opinion, published on October 28, 55% of Gazans and 87% of West Bank Palestinians oppose Hamas disarmament. And according to a survey published in late July by the right-wing newspaper Israel Hayom, 52% of Israelis support the settlement of Gaza.

The attitudes of both sides have changed since the beginning of the war and can change again, for better or for worse. The day after the Israel Hayom poll, a Times of Israel poll asked participants if they supported the annexation of Gaza (as opposed to settlement) and 53% answered no. But all of this will complicate the work of Steve Whitkov, Jared Kushner and other Trump aides tasked with bringing the peace deal to fruition. They will have to maintain an iron fist on both sides if they want the peace process to continue and fully engage the Arab allies, on whom both the reconstruction of Gaza and the broader security of the Middle East depend.

If Trump fails to do so, his dream of a historic peace in Gaza – under his leadership – that will lead to the normalization of relations between Israel and its wealthy friends in the Gulf will remain just a dream.

BloombergOpinion