in-cyprus 1 November 2025

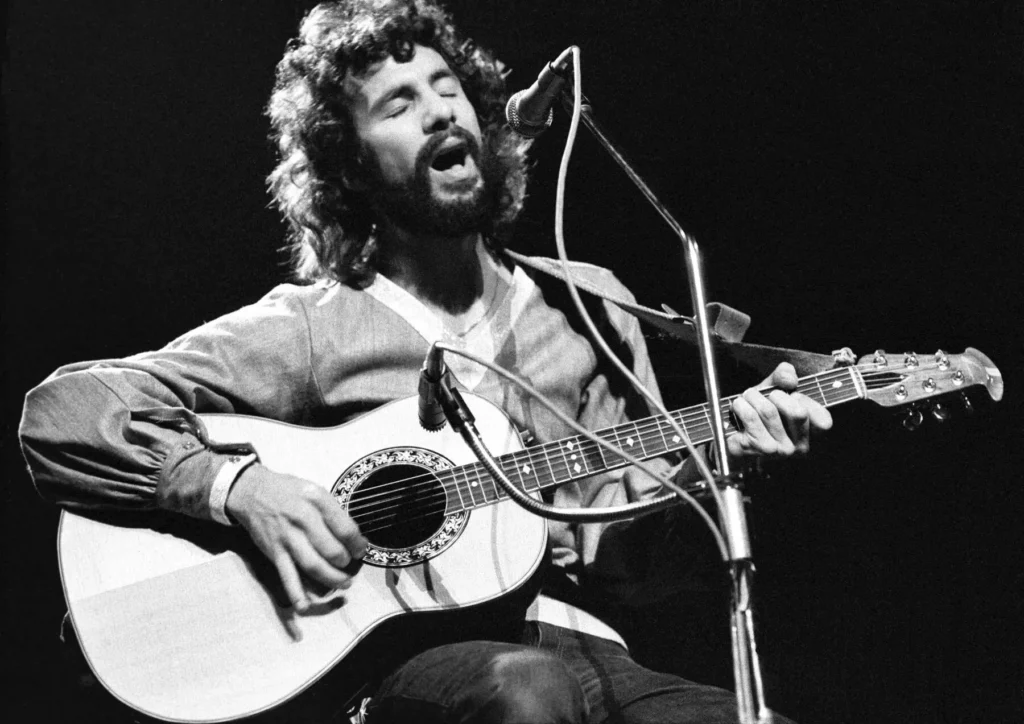

Yusuf Islam, the British-Cypriot musician who walked away from stardom as Cat Stevens in 1977, has released a memoir examining the spiritual journey that led him to abandon—and eventually reclaim—his music.

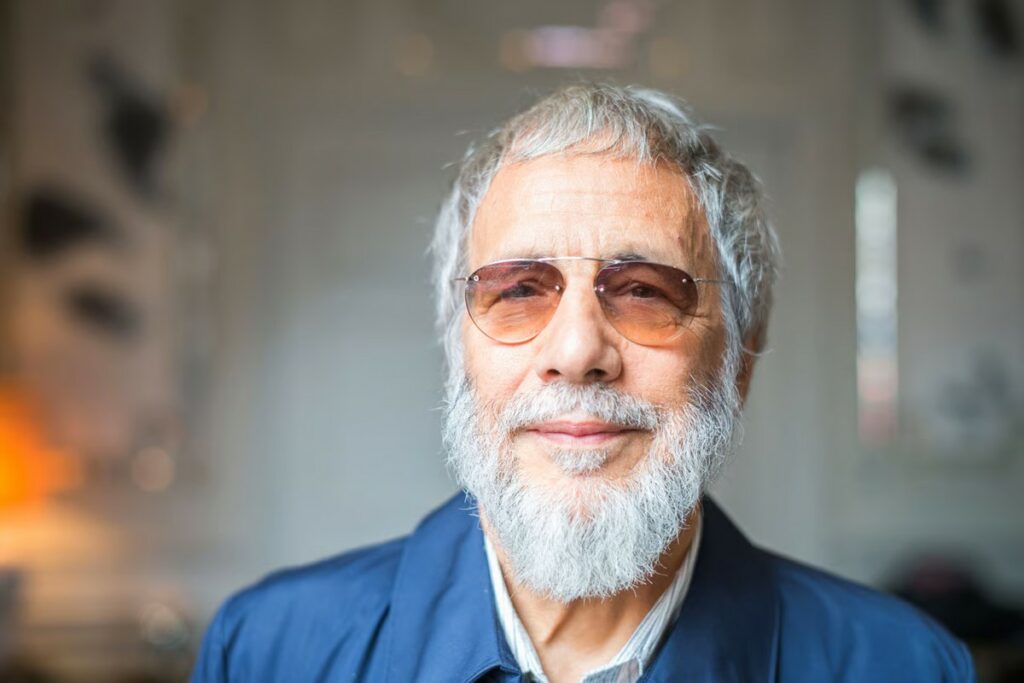

The 77-year-old artist, born Steven Georgiou in London to a Cypriot father and Swedish mother, published “Cat on the Road to Findout” in early October.

In a recent profile in the New York Times, Islam speaks candidly about the faith that rescued him, the “crooked paths” that distanced him from the world, and the music that ultimately never stopped defining him.

The book is not simply an autobiography but a narrative of seeking, faith and reconciliation, written with humour, sensitivity and deep self-awareness.

From pop idol to near-drowning

Islam’s story reads almost like myth. Young Steven Georgiou grew up above the Greek restaurant his family ran in London’s Soho. He signed his first record deal at 18 and became a pop idol by 20. Fame arrived quickly, along with exhaustion. In his twenties he fell seriously ill with tuberculosis—an experience that turned him towards serious, existential questions about the meaning of life, he said.

The defining moment came in 1975 during a California holiday, when Pacific waves swept him out to sea and he nearly drowned. He believed he had seconds to live and prayed that if he survived, he would devote himself to God. A wave pushed him back to shore—an experience that changed him forever.

Months later, his brother David gave him a copy of the Quran he had bought on a trip to Jerusalem. Islam read the first pages and felt he had found the path he was searching for. In 1977 Cat Stevens converted to Islam, took the name Yusuf Islam and withdrew almost entirely from music. He released his final album as Cat Stevens, “Back to Earth”, in 1978—a farewell without fanfares.

Three decades away from the spotlight

For the next 30 years, the musician lived away from public attention, devoted to spirituality, his family and charitable programmes for children and refugees. In 1981 he sold nearly all his musical equipment and donated the proceeds to two charities. As he now admits, influenced by a religious pamphlet circulating in South Africa at the time, he had been convinced that Islam forbade music—a belief that frightened him deeply.

His relationship with the public sphere was often contentious. His statements around the notorious fatwa against Salman Rushdie in the 1980s were misinterpreted, sparking reactions that stigmatised his reputation for years. In his book he acknowledges he often failed to handle what he said publicly with prudence, admitting he was inexperienced and did not know how to speak in ways others would understand.

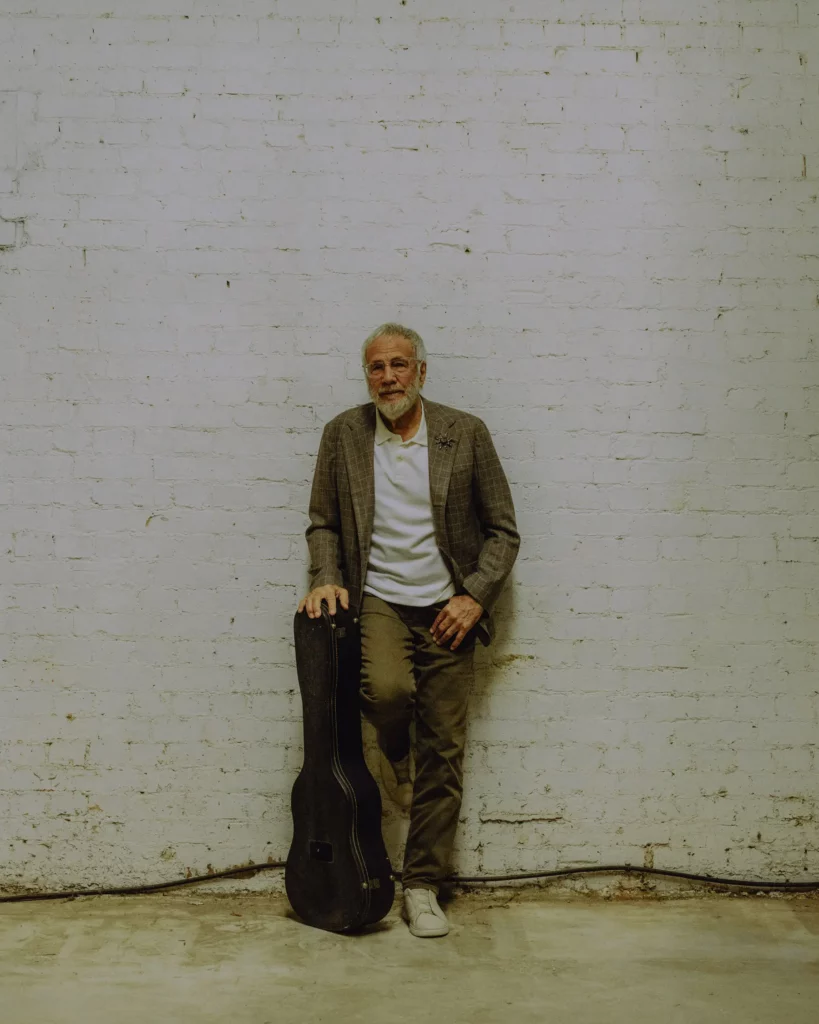

A guitar brings him back

His return to music came almost by accident in the early 2000s when his son, Muhammad, brought home a guitar. Islam picked it up and began playing. That simple act reopened the path to creation.

That same night, his younger sister Amina asked him to sing his old song “The Laughing Apple” from the 1967 album “New Masters”. It was the first time his children had heard his voice accompanied by guitar. By the next morning he had written a new song, according to Muhammad.

The rebirth was not sudden. From the mid-1990s Islam had been carefully testing the limits of his relationship with music. In 1995 he recorded “The Life of the Last Prophet”, a work combining spoken word with traditional Muslim hymns (nasheeds) accompanied only by percussion. The album achieved enormous success in the Muslim world, and he founded the Mountain of Light record label, following up with children’s songs and spiritual works that united faith and art.

Since then, Yusuf Islam has recorded six new albums, collaborated with Dolly Parton and Paul McCartney, and curated deluxe reissues of his classic records “Tea for the Tillerman” and “Mona Bone Jakon”.

Explaining things is a dry way of communicating, he told the New York Times. He is in his element when singing his heart.

Between poles

His renewed relationship with music led Islam to a deeper reinterpretation of his faith. From his early years in Islam he had decided not to join any school or sect of Sunni Islam, saying he saw no borders and always returned to the concept of unity. Over the years he realised he did not need to follow others’ strict interpretations to remain faithful.

In 2014 he published “Why I Still Carry a Guitar”, a book explaining to the Muslim community his continuation of his artistic path—a step that eventually led to writing “Cat on the Road to Findout”.

There were threats from certain circles of the religious community, he said. They told him it was dangerous to put himself forward, to “show off” his talent. But his art is something much deeper than that, he said.

The New York Times notes that for 70 years Islam has moved between opposite poles—famous and reclusive, believer and questioner, Cat and Yusuf. His recent albums are released under the signature Yusuf / Cat Stevens as a symbol of reconciling his two selves.

Haunted by Gaza

Current events find Islam deeply troubled. The war in Gaza represents a moment of testing for all humanity, he said. He was accused in the past, unfairly as he insists, of having ties to Hamas—a matter that caused him problems with his US visa until 2006.

The new generation witnessing this destruction will never forget it, he noted.

Today he confronts his past with irony and reflection. He remembers the young Cat Stevens who did not know how to explain himself to the media, who spoke awkwardly on stage between songs.

He was searching for answers, and a large part of those answers lay within music, he said. When he found them, it was natural to fall silent for a while. Only when he felt he was holding something true could he return and share it.

“Cat on the Road to Findout” is the sum of all this: a life between fame and silence, faith and doubt, Cyprus of his origins, and the world that ultimately embraced him.

(information from The New York Times)