Filenews 5 November 2025 - by Liam Denning

Jacques Nasser, the hardline former CEO of Ford Motor, is said to have once summed up the situation in his industry as follows: "We make cars and everyone else makes money." A bit abrupt, but Nasser's black humour remains an essential framework for understanding carmakers who are still facing a chip shortage (plus a disruption in aluminium supply) amid an ongoing trade war.

The tension between governments, customers and shareholders over the expectations of each side from this industry in the 21st century has taken on enormous proportions. If higher prices are to be avoided, the industry's workforce can turn into a decompression valve.

Nexperia Holding is a Chinese chipmaker based in the Netherlands, which is at the center of a feud between the Netherlands, with the encouragement of the United States, and China. These are not the state-of-the-art semiconductors that AI giants use for their new advanced models, but basic, so-called "old" technology – the technology behind about 95% of the chips of an average vehicle. Nexperia is not the only supplier of these chips. However, its recent shutdown has led major car manufacturers and suppliers, such as Honda Motor and ZF Friedrichshafen, to already slow down their production. Ford CEO Jim Farley has warned of production losses if the dispute is not resolved soon. Signs of a possible truce appeared this weekend.

It may seem strange that the automotive industry is in such turmoil because of a single event, just a few years after the pandemic that caused a chip shortage and led to a drop in global car production by about 12 million units. I refer you to Nasser's quote. This is a mature, expensive and highly competitive industry, where brands matter, sometimes very much, but price is the most important criterion for most car buyers. This in itself reduces profit margins, but is exacerbated by the social burden borne by their factories. "Capacity never goes away," says Glenn Mercer, an independent consultant and president of GM Automotive, as governments often work with workers to prevent lockdowns.

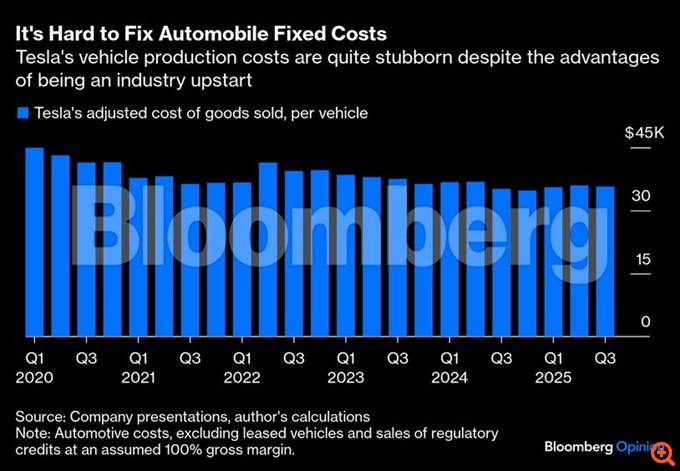

All of this leads to overcapacity and fixed fixed costs. This is not only a problem for "dinosaurs". Take Tesla, for example, where Elon Musk boasts of reinventing the way it is produced, but the average cost of building a vehicle has remained virtually stable over the past four years, at around $36,000. And this despite the fact that Tesla does not have traditional working practices, it has high leverage due to the structural reduction in battery costs, and 40% of its assembly lines are located in China.

In this industry, everything surplus is a luxury and "just-in-time" production is a necessity. Holidays are a problem, but also a characteristic. Automakers are diversifying as much as possible, of course, but the same economic conditions are pushing suppliers to consolidate.

Additionally, as vehicles become increasingly complex, changing suppliers in case of need becomes more difficult. A relatively simple diode from one of Nexperia's competitors can take weeks or months to test and be approved before it can be used. Similarly, as Ford searches for alternative aluminium for its F-150 trucks after the recent fire at a supplier's plant in upstate New York, it cannot accept any quality for its products. Looking for alternatives was easier when globalization was at its peak, but even Canadian aluminium is now subject to U.S. tariffs. Nexperia's chip supply is itself a victim of the trade war, not a virus.

Automakers are now called upon not only to produce vehicles that are affordable and profitable, but also to strengthen national security through reshoring, the return of production, thus boosting employment. This is very challenging for an industry that has spent decades struggling, and often struggling, to win back the cost of capital, squeezing labor costs, and looking for competitive suppliers around the world. So far this year, Ford and General Motors have done well, albeit in comparison to lowered earnings expectations.

Reinventing supply chains from abroad in the US is the ultimate form of "redundancy" and will therefore ultimately lead to inflation. This is not criticism. To a certain extent, we can either enjoy nominally cheap products or pay a premium against the dismantling of the industrial zone and the intimidation tactics of the outside. However, in order to remain competitive and with an eye on the day when protectionist tendencies fade and Chinese automakers may gain access to the U.S. market, the industry needs to rethink its strategy.

One possible outcome is greater automation. As things stand, there are indications of a growing interest in robots, and I don't just mean Musk's monologues about Optimus' touted dexterity. Lear, a first-class automotive supplier focused on more everyday technologies such as heated car seats and wiring, has received a new boost from the disruption brought by the tariffs. It recently announced a new exhibition in suburban Detroit to showcase the so-called "lights out" construction – without human labour – of seating systems. Traditional assembly involves "several dozen people" spread across 20 stations, according to comments by Frank Orsini, Lear's head of the seating department.

Replacing workers with robots is not necessarily a panacea. Mercer points out that, if all else remains the same, shifting more production toward machinery could increase the burden of fixed costs, replacing variable labour costs with investments in assets. On the other hand, the threat of automated competition could cause greater volatility in these labour costs. Breaking with the past, as is happening now with supply chains, but at the same time insisting on the practices of the past is an unrealistic scenario. Reshoring requires reinvention rather than mere replication, and the promise of reshoring is likely to be fruitless.