Filenews 24 October 2025

By Lionel Laurent

The book Senkaku Paradox describes how small stakes can lead to big conflicts in an era of great power rivalry. Although this is military terminology, it can be applied to the escalating economic confrontation between the Netherlands and China over the microchip company Nexperia. The growing risk of chip shortages caused by political strife – rather than disease or armed conflict – should serve as a warning for Europe to address its vulnerabilities in trade wars.

Last week, the Dutch government took control of Nexperia, based in the Netherlands and owned by China, citing a Cold War-era law designed to ensure access to critical goods in the event of an emergency. These supplies are low-tech, such as transistors and diodes, but they are critical for, essentially, everything from cars to medical equipment – and Nexperia accounts for 10% of the global market. The justification for this bold but risky move was some evidence of conflicts of interest and an attempt to shift assets by Chinese parent Wingtech Technology Co. Ltd., as stated in court documents.

However, if this law is being implemented for the first time, it is due to a geopolitical context that is impossible to ignore. Chip exports are not simple, and Wingtech was included in the US commercial blacklist late last year. U.S. officials even made it clear in The Hague in June that Nexperia's Chinese CEO should be replaced. This is not the first case of American pressure on Dutch technology, with ASML Holding NV's chip-making machines already subject to export controls.

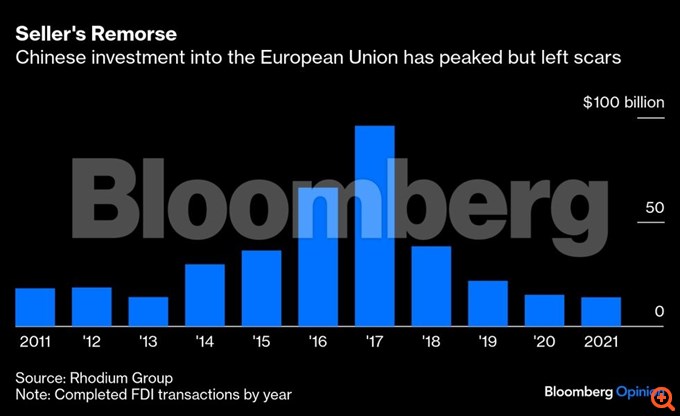

The speed of this move also shows the extent of the panic in Europe over its dependence on China for rearmament and reindustrialization – while also regretting the fact that it has signed billions in asset sales to China (including Nexperia) over the past decade. Beijing accounts for a third of the main chip supplies – it also mines about 60% and processes about 90% of the world's rare earths, critical components for electric cars and fighter jets. The seizure of Nexperia came just days after China increased restrictions on rare earth exports, ostensibly targeting the U.S., but also hitting Europe.

The catch here is that dealing with dependency comes at a cost, in this case retaliation from Beijing with restrictions on shipping products abroad from Nexperia's factories in China, which prompted European automakers to warn of shortages. What was supposed to maintain Nexperia's value and customer access has made both now seem fragile. European players, such as Volkswagen AG and Robert Bosch GmbH, are now trying to find alternative sources for chips. The Dutch government also inherited a corporate conundrum: Nexperia is too Chinese for the Dutch, too Dutch for the Chinese, and too politically sensitive to be easily sold to a new owner – recall that Chinese regulators blocked the sale of its former parent NXP Semiconductors NV to US-based Qualcomm Inc. in 2018.

In the short term, we can expect pressure from Brussels technocrats and industrial lobbies to defuse tension. Good luck. The Dutch parliamentary elections are just a few days away, and this is an issue that evokes strong emotions for a country that the sale of Nexperia in 2016 let go of more innocent – or naïve – times. At the same time, China has decided that Europe is fair game for a tougher approach.

In the long term, however, Europe needs to find more sustainable ways to deal with critical dependencies. In the same way that it is vulnerable to the Trump administration's moves, given its dependence on U.S. defense and technology companies, it has also done very little to reduce the risk to supply chains from a more assertive China. Its plans for chips and batteries did not receive the proper trust, nor did the cash. The EU is expected to miss its goal of doubling its share of chip production to 20% by 2030 – meanwhile, the signs of failed Swedish battery start-up Northvolt AB are still visible.

A combination of moves will be needed: More investment at home and more measures to tackle artificially cheap imports, such as tariffs on electric cars or steel. Billions of new defense spending budget funds should be used to break China's stranglehold on critical raw materials, says Joris Teer of the European Union's Institute for Security Studies. At the same time, greater unity among European member states, and the influence of Berlin, will also be necessary.

Hopefully, Nexperia serves as a warning of what to avoid rather than a prelude to what is to come.