Filenews 8 August 2025

By Tobin Harshaw

The dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima exactly 80 years ago is something to remember but not celebrate. It was also the beginning of a new era: the individual age. Growing up in the final years of the Cold War, my generation did not live with the sense of threat and the "duck-and-cover" exercises of Bert the Turtle that baby boomers experienced. But both were blessed by the absence of a large-scale war, conventional or nuclear, between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

Which brings to the fore an 80-year-old question: Did the development of nuclear weapons keep the peace during the Cold War? And if so, what explains this paradoxical result? The simple answer is unsatisfactory: It's complicated.

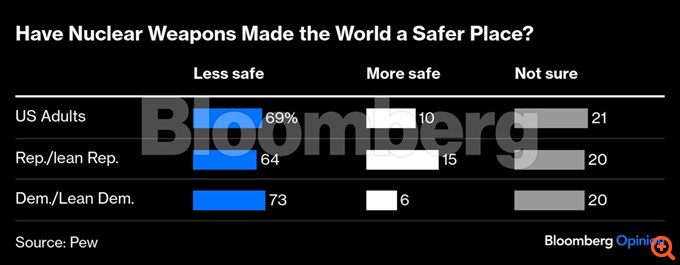

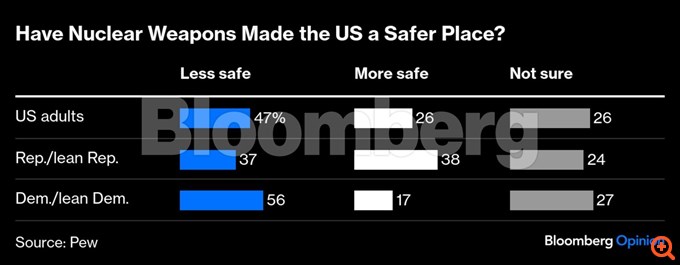

Harry Truman, the president in charge of Hiroshima, insisted that the bomb "would become a powerful and dynamic influence in the direction of maintaining world peace." A recent Pew poll shows that this view has changed: 69 percent of respondents in the U.S. said that the development of nuclear weapons "has made the world less safe."

But perhaps this is the wrong question. After all, a weapon remains a material thing – the real question is whether those responsible handle it wisely. (In this case, don't use it at all.) And by "wisdom," I don't just mean believing that a nuclear war, while not unthinkable, is unsustainable. Rather, the real wisdom is to recognize that avoiding a nuclear winter required a remarkably clever series of strategic changes by American leaders during the 45 years we've lived on the brink of a cliff.

We often see Cold War strategy through the eloquent phraseology of early theorists of individual conflict, many of whom worked for the RAND Corporation. Among them were economist Thomas Schelling, an expert in game theory, and physicist Hermann Kahn, who popularized the idea of "mutually assured destruction" – the idea that the dire consequences of a massive nuclear war on either side would prevent it from happening.

Perhaps. Gambling can be a good way to consider economic decisions, but it is dangerous for geostrategy: It is traditionally based on the idea that neither side has an incentive to change strategy unilaterally and may assume that states are playing a zero-sum nuclear game. The politics and governance of a country are not played like this*.

Mutually assured destruction has a stronger grip on reality, but, in addition to its bad branding, it has been widely treated in static terms: the perpetual presence of weapons that destroy civilization and are ready for use. This model cannot stand, for example, if even one side believes that escalation can be ended by using tactical, lower-effective, "battlefield" weapons.

Abstract theories are all well and good, but let's admit that politics, diplomacy, military strategy, soft power, and even luck, all of these, are the product of the actions of people who change their minds and adapt to the new realities, just like their successors with the status quo they inherit. So, if we want to say that a mass of nuclear weapons has kept the peace for decades, we have to focus on the men in power (unfortunately, they are all men) and not on the missiles.

The American approach to deterrence has had almost as many nicknames as presidents in these 45 years: mass retaliation, New Look, Flexible Response, strategic stability, Madman Theory, "limited" nuclear war, and so on. Some were overlapping and all contributed to the nuclear balance, but none determined it. On the contrary, all together they show that if nuclear power kept the peace, it was only through continuous adjustment based on changing geopolitics, advances in conventional military technology, generational change, domestic politics, and political conflicts (i.e., bureaucratic back-stabbings).

Bookshelves and hard drives groan from the multitude of discussions about this story, which defies easy condensing**. But for the purposes of the article, it's worth looking at two presidencies that came at the end of the Cold War: those of Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.

Carter, a former Navy nuclear engineer, came to power in 1977 as a nuclear peacemaker: In a speech to the United Nations General Assembly he called for "a truly nuclear-weapon-free world" and warned that if the proliferation of nuclear weapons accelerated, "the world we leave to our children will ridicule our own hopes for peace." And it tried, but failed, to reach a modest arms limitation agreement with the Soviets, known as SALT II.

However, how can this keep up with a president who pressured Congress to authorize the development of a "neutron bomb," which instead of creating a massive explosion, would release vast amounts of deadly radiation? (Equally important: He withdrew the program due to political ambivalence among European allies.)

In addition, Carter (led by his Secretary of Defense, nuclear physicist Harold Brown) issued a series of presidential directives to modernize the nuclear arsenal. One of them was the controversial PD-59, which described the "countervailing strategy" – essentially a war plan – for a nuclear conflict with the Soviet Union. By targeting the leadership and military installations of the USSR rather than the population centers, it escaped the MAD (Mutual assured destruction). It also showed how Carter quickly learned that his ambitions to abolish nuclear weapons were futile, and that the threat of limited nuclear war may be a better deterrent than stockpiling ICBMs capable of destroying civilizations and unlikely to be launched (at least intentionally).

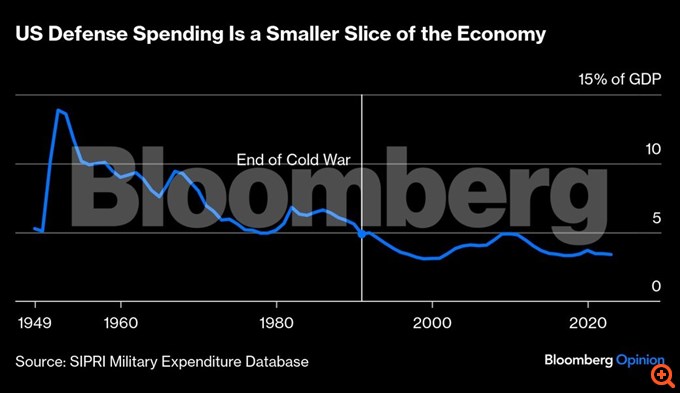

This new doctrine was in line with Carter's support for the Pentagon's broader doctrine of conventional forces, a plan to focus less on the quantity of U.S. material and manpower and more on the quality made possible by the U.S.'s enormous advantage in technology, computing, and manufacturing. The U.S. needed the bomb less and less—the danger was that the USSR became more and more dependent on it.

Then there is the curious case of Ronald Reagan. As much as his opponents wanted to call him a warmonger, he had been in favor of banning nuclear weapons as early as 1945, when the Warner Bros. studio prevented him from helping lead an anti-nuclear rally in Hollywood. He assumed office on the grounds that the concept of mutually assured destruction was abominable.

Reagan's strategy was the "carrot and whip." With the whip, he symbolized what the Washington Post (unfairly) described as "a war machine economy in an era of restless peace." It promoted the development and installation of ICBM Peacekeeper missiles, which continue to form the backbone of America's ground deterrent force.

Perhaps his most important, though controversial, success was the implementation of a plan initiated under the Carter administration to place American Pershing II cruise missiles and tactical nuclear-warhead surface-to-surface missiles on Allied territory – including West Germany, supposedly to counter the Soviets' new SS-20 ballistic system. More than a million people protested the plan across Europe in October 1983, but Reagan read the climate and kept the fragile coalition of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, and French President François Mitterrand. The great historian Timothy Garton Ash once told me that the combination of hard and soft power, personified by these missile deployments and the human rights initiative of the Helsinki Agreement, had a significant impact on the Soviet Union.

The carrots offered to Moscow were extremely small, reflecting the hardening of the Soviet threat and the military, economic, and cultural dominance of the West. Reagan's clever dealings with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who recognized that he had few cards to play, first succeeded in securing the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Weapons (INF) treaty in 1987 and laid the groundwork for the first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), which was completed in 1991 under President George W. Bush.

This brings us to the most talked-about and perhaps misunderstood initiative of the Reagan era: the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), or "Star Wars," as its critics called it. The space system was intended as a shield to defend the U.S. from Soviet ICBMs, isolating the country from the greatest nuclear threat. In the minds of Reagan and his advisers, he was the ultimate peacemaker: If the Soviets were unable to strike the U.S. with massive nuclear strikes, there would be no reason to retaliate. Opponents scoffed at its technological weakness (a good argument) and said it would upset the balance of power in the nuclear age – a less obvious and rather strange conclusion from those who thundered the status quo of balance through MAD.

As we know, SDI never happened. And with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, we entered what we hoped would be a kind of post-nuclear world order. Until now.

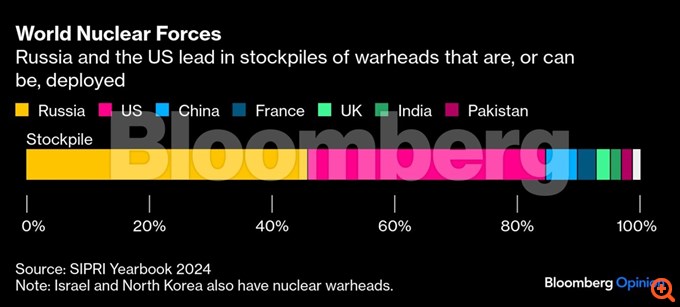

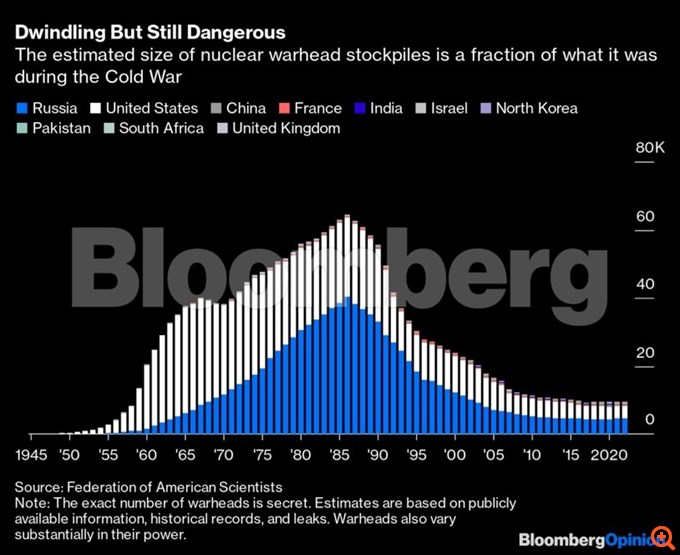

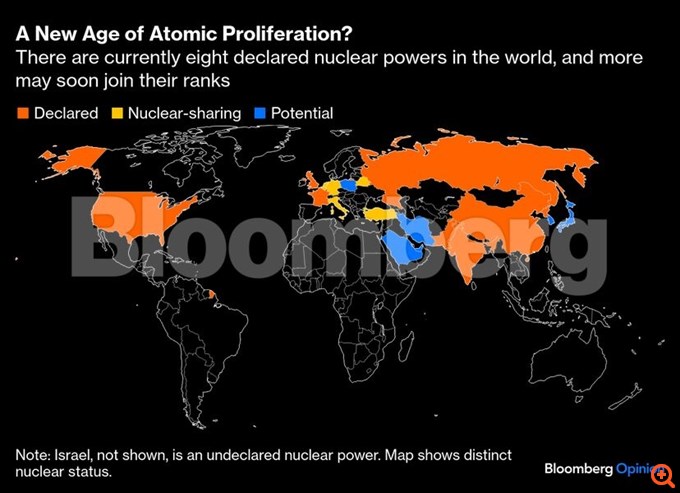

With Russian President Vladimir Putin threatening to use battlefield weapons in the conflict in Ukraine and potentially withdrawing from the INF agreement, North Korea perfecting its ballistic missiles, and China building a world-class arsenal in record time, we have reached what my colleague Hal Brands calls the New Nuclear Age.

So, in this new Cold War, how can the U.S. redraw the lessons of the old and adapt to changing circumstances in a way that discourages adversaries without inflaming tensions?

Here are a series of suggestions, for starters:

- Encourage allies, including South Korea, Poland and, unfortunately on this black anniversary, Japan, to start researching and developing their own nuclear weapons programs – but not necessarily to build a bomb, until we clarify the China-Russia response.

- Make tactical weapons on nuclear submarines the central element of deterrence. Unfortunately, China's rise makes it necessary to upgrade America's intercontinental missiles (part of a $1.2 trillion program launched under Barack Obama), but with the air force becoming increasingly vulnerable to drones and other technologies, the new B-21 long-range bomber program should be limited to 100 under contract.

- Try to bring China into a global non-proliferation or arms control regime – an effort that is almost certainly doomed to failure, but which upgrades the title of "good boy" for America. Also, try to save the START treaty with Russia before it expires next year – also unlikely to happen, but it's worth trying.

- Conclude a formal defense treaty with Saudi Arabia (and the United Arab Emirates) in exchange for recognition of Israel. This would prevent Arab states from pursuing their own nuclear programs while keeping Iran's program in check. But that is waiting until the war in Gaza is resolved.

- Forget President Donald Trump's notorious nationwide "Golden Dome" missile defense, which is no more technologically viable than its predecessor, SDI. Instead, invest much more in the West Coast Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system designed to take down a North Korean attack, thus advancing the technology for a nationwide shield.

More importantly, the country must survive Trump's efforts to undermine the U.S.-led world order — and decades-old deterrence strategy — and continue to adapt its nuclear policy to changes on the global chessboard. Human action remains the antidote to technological determinism. If a future situation designed by smart policymakers involves the extermination of any of these five "recipes," no one will be happier than I am.

*For a much more specialized view on this, see the two parts of the interview with MIT's Vipin Narang here and here.

**The literature here is endless. I would recommend Lawrence Freedman and Jeffrey Michaels' book The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy.

Rendering – Editing: Lydia Roubopoulou