Filenews 24 December 2024 -by Javier Blas

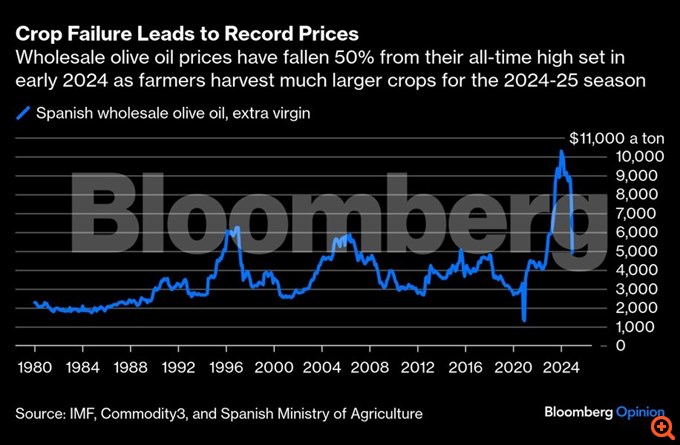

It's over – the olive oil crisis that hit my kitchen is starting to fade. After two consecutive years of poor harvest, Spanish olive producers are now gathering enough fruit to ensure a good supply in 2025. Wholesale prices have fallen by around 55% from their all-time high in February – retail prices will soon follow.

However, I do not expect a return to the low prices of the last 20 years, for two reasons – one is temporary, the other, structural. Few pay due attention to these factors.

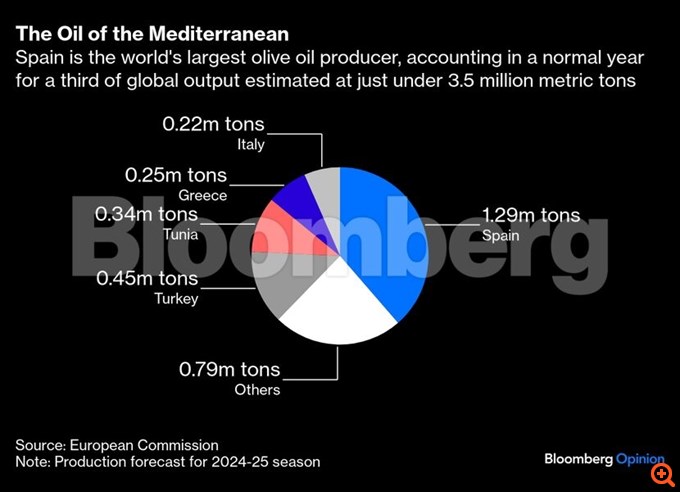

Olive harvesting is underway in Spain's Andalusia region, which accounts for about a third of global production. Usually, the volume of the harvest peaks just before Christmas, and so far we have a very good picture of both quantity and quality.

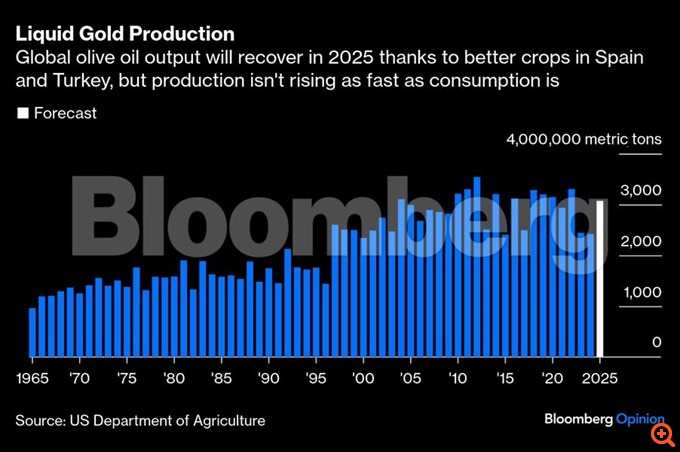

Thanks to the better harvest, Andalusia is likely to deliver about 1 million tons of olive oil in 2024-2025, a 77% increase over the previous year. If we add other regions of Spain, as well as good harvests in Greece, Portugal, Tunisia and, most importantly, Turkey, global production is expected to recover to about 3.4 million tons, from less than 2.6 million tons in the period 2023-2024. Among the major producers, only Italy has yet to recover, as it battles a pathogen that "kills" the country's olives.

Once it became clear that the harvest was much larger than in the previous two years, everyone rushed to sell.

The cost of high-quality Spanish extra virgin olive oil on the wholesale market fell to about $4,250 per tonne, more than halving the all-time high of more than $10,000 per tonne recorded in February. On supermarket shelves, the price of a litre could soon fall from €10 to around €5.

The fall in price is a great relief for southern Europe, whose inhabitants consider olive oil an integral part of their lives – from food to customs that have developed over millennia on the shores of the Mediterranean. For many families in the area, its higher price symbolized the struggle against runaway inflation. Every week at the supermarket, I moaned about the cost and hoped for a better day.

For the Spaniards, it was a real crisis. Generously pour olive oil into our food: The average Spaniard consumes about 14 liters in a normal year. If multiplied for a family of four, a household in Spain would spend more than €450 ($471) in a year based on the average retail price of 2023-2024. (The Greeks are the champions of olive oil, consuming more than 20 liters per person per year. The Italians come right after the Spaniards, consuming about 11 liters. The British and Americans "sprinkle" their food with about a liter of oil per year.)

Consequently, the fall in wholesale prices is a huge breather – a news item dominating evening news in southern Europe. However, I am concerned that it seems somewhat excessive. And here comes the bad news that I referred to earlier.

First, temporary factors. After two years of poor harvests, agricultural cooperatives in Spain were in financial trouble, so they sold their crops as early as they could, causing the market to collapse. However, sales will eventually run out, putting a floor on prices. Moreover, global olive oil stocks have been decimated and a good harvest is not enough to renew them. In Spain, inventories in 2023-2024 reached about a quarter of the typical level. Globally, olive oil stocks last season fell to a 57-year low, about half the average of the past two decades.

It will take several generous years before stocks are replenished to desired levels for prices to return to pre-crisis levels.

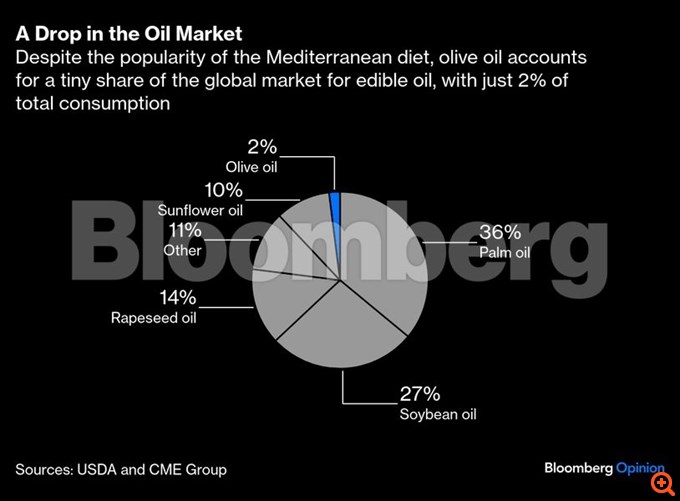

Secondly, structural factors. Olive oil is a victim of its own success. With the Mediterranean diet gaining ground internationally, olive oil consumption has doubled in the last 30 years. And this trend looks set to continue, despite high prices.

As beloved as it is in southern Europe, it accounts for a small percentage of the world's consumption of edible oils. In 2020, it accounted for less than 2% of the global market, on par with cottonseed and coconut oil. Palm and soybean oil together account for 65% – sunflower and rapeseed oil together account for another 24%. Therefore, olive oil has room to easily gain market share. The problem is that it can't: Supply is limited, and any increase in popularity will force prices to rise to higher levels.

How sought after is olive oil becoming? A lot, the stats say. In the US, demand has grown more than 300% over the past three decades. Or consider France, the country of butter, where demand has increased by 400% since 1990 and today its consumption equals that of Greece. The UK saw a spectacular leap – probably helped by the fact that I moved from Madrid to London a few decades ago. Since 1990, British olive oil consumption has increased by about 1,100%. Similar growth is seen in emerging markets, where olive oil penetrates countries such as Brazil. Demand in these new consumption centres appears to be less price sensitive than in the main Mediterranean markets.

With low inventories and depressed demand, olive oil prices cannot fall significantly. The crisis is over, but the years of abundance seem far away. Maybe that's not a bad thing: For the first time in a long time, olive oil producers, long the weakest link in the supply chain, are poised to see better days. If you like olive oil, it's a reason to celebrate.

Performance – Editing: Lydia Roumpopoulou