Filenews 27 November 2024 - by Marcus Ashworth

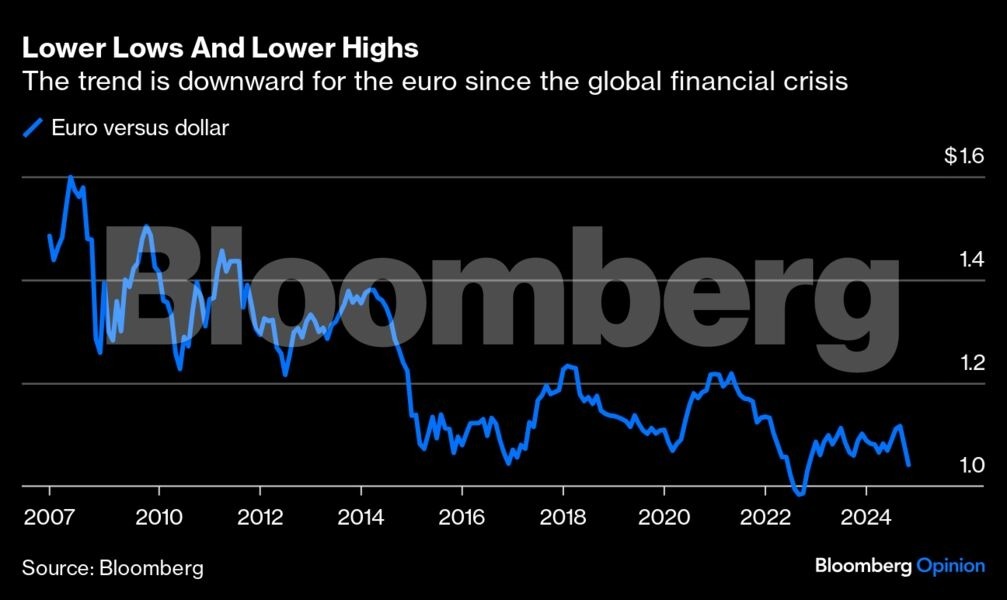

Dark clouds have been gathering in recent weeks in the eurozone in the wake of a series of bad economic data. The political situation, finances and interest rates in the European Union are worsening the euro, driving the common currency towards parity with the dollar. Even Europe's largest asset manager, Amundi SA, says a 1-to-1 rate could happen by the end of the year. Europe may not be in an existential crisis, but it is certainly in a difficult position.

The euro is sinking into the wake of a mighty US economy, capital markets and dollar. To everyone's dismay, he seems to have lost control, with any course dictated, it seems, by what President-elect Donald Trump can — or can't — do. In stark contrast to the picture of stagnant growth in Europe, the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow points to a 2.6% increase in U.S. renewables in the fourth quarter – suggesting a positive backdrop for further dollar gains.

Are there 'dark days' coming for the euro?

The euro has fallen to a two-year low against the dollar. It's not the only one buckling in front of the dollar. The pound is also subdued, as the UK also announces rather negative economic data. Although the common currency is not yet in free fall, there is no clear hope on the horizon. Any recovery in the foreign exchange market is far more likely to come from limited gains for the dollar than from domestic developments.

The political landscape is a mess, with Germany now following the path mapped out by France. The two largest European economies, coincidentally, are also leading the economic downturn, with German GDP in the third quarter revised down to 0.1%. Business activity in the eurozone contracted to 48.1 in November from 50 the previous month, falling for the fourth time this year – this time, it looks set to struggle to recover to growth. The PMI for the eurozone manufacturing sector fell again to 45.2, with the sector clearly in recession. Based on this gloomy picture, both the French and German indexes fell to 43.2. Even more worrying is the drop in services to 49.2 from 51.6 in October. Where will the growth come from now?

France is walking a tightrope, along with Italy, facing how the European Commission will decide to handle blatant overspending, which violates EU deficit rules. French Prime Minister Michel Barnier is struggling to get the 2025 budget package through the National Assembly.

Barnier can bypass parliament, but if his government subsequently loses the confidence vote, the entire political house of cards could collapse. Brussels may decide it has no choice but to send him back for a "review". Fiscal rules are necessary as they hold together the entire euro project, even if it is not pleasant to curb government spending at a time of recession and falling tax revenues.

Germany's industrial problems are well known, but any future possible change to its debt brake must be accompanied by a new economic deal for the eurozone. The approach of an inevitable circumvention of the rules has characterised the EU throughout its adventurous journey. The German Constitutional Court is a major obstacle to ambitious plans unveiled in September by former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi. Hopes for a repeat of the €800 billion ($840 billion) post-pandemic recovery plan – possibly under the guise of defence measures and the climate-neutrality objective – may be dashed. Nevertheless, realpolitik dictates that Brussels react before it is too late.

This brings us to the ECB. President Christine Lagarde on Friday called on the bloc to organize on the still-nonexistent capital markets union. However, the Governing Council sent out an even more serious message – monetary policy cannot shoulder the full economic burden – interest rate cuts will be ineffective unless accompanied by fiscal efforts.

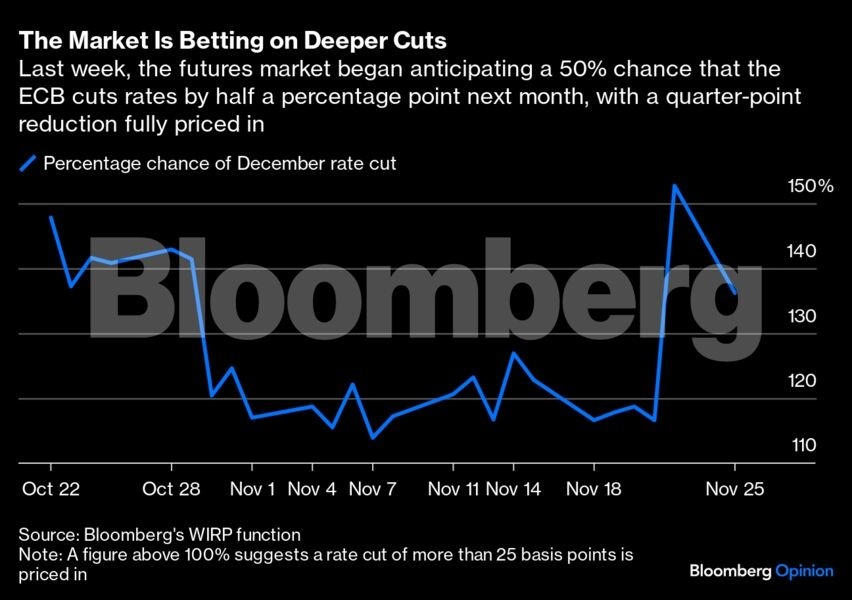

When the doves shout – as several ECB policymakers did last week – the futures market moves in the direction of a more aggressive cut in the official deposit rate, with expectations now shifting by half towards a 50 basis point emergency move. A quarter-point cut to 3% at the Dec. 12 meeting was hinted at at the last meeting — Frederik Ducrozet, head of macroeconomic research at Pictet Wealth Management, notes it may have been a policy mistake.

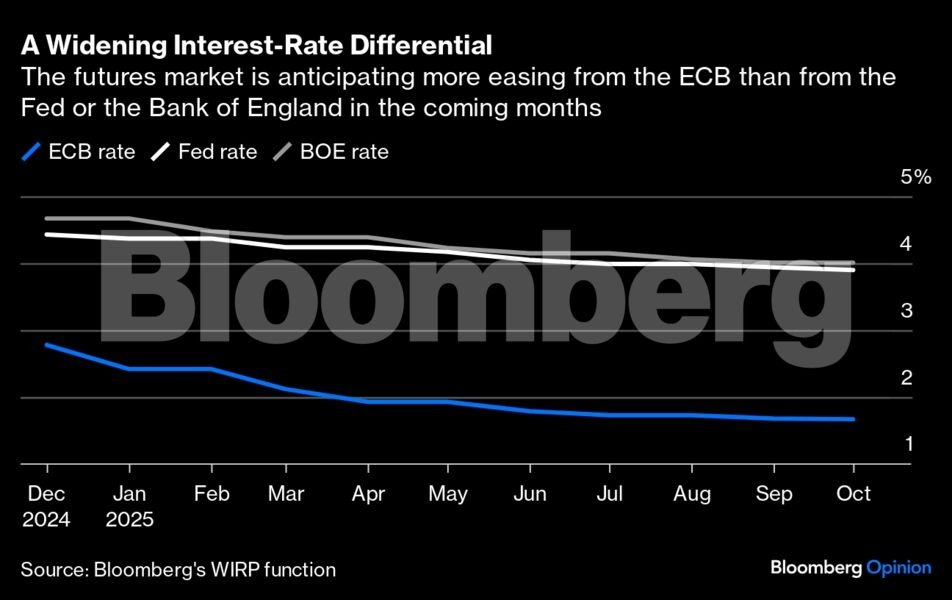

Eurozone inflation data for October due on 29 November is likely to show an uptick in the main readings, reflecting the sharp increase seen in the UK. This may prompt hawks at the ECB to oppose accelerating the pace of easing to achieve the mythical "neutral" interest rate to balance employment and prices. Current estimates put this figure somewhere close to 2%, the ECB's inflation target. However, this brings us to the core of the question 'why the euro is weak'. The "neutral" interest rate for the eurozone is much lower than in the US or UK.

Futures forecast the ECB rate to reach 1.75% by next summer, halving the tightening by 450 points from July 2022 to September 2023.

The lesson to be learned from the pandemic is that a mix of fiscal and monetary stimulus can be extremely strong. The combination supported the euro area economy, but it lasted too long and stoke inflation. The ECB may be forced to cut interest rates more forcefully – but if the euro is not to fall sharply against the dollar, Brussels needs a fiscal plan B – and soon. Currency pairs often revolve around relative interest rate differentials – but growth expectations are the real driver, and by this measure, a fall in the euro to or below the value of the dollar seems more likely.