Filenews 14 December 2023 - by Marc Champion

Russia's invasion of Ukraine has not turned out as Vladimir Putin had hoped, but it has proved inconceivably beneficial to his colleague, the authoritarian leader of neighbouring Azerbaijan. President Ilham Aliyev has never been as secure politically as he is today.

Unfortunately, this success only adds to evidence, assuming more was needed, that when dictators feel strong, they tend to use their increased confidence for repression rather than political and economic reform.

Multiple wins

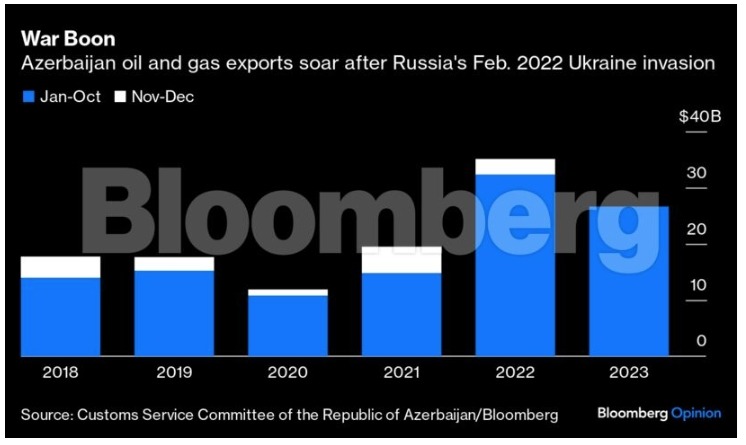

Aliyev has gained a lot from Russia's invasion on multiple fronts. In July last year, it signed a deal with the European Union to double Azeri gas exports to the 27-nation bloc as the latter struggled to find new energy sources to fill the gap left by Russian supplies lost due to sanctions.

New infrastructure needs to be built to make this possible, but increased sales and with it prices increased revenues from the former Soviet country's oil and gas sectors from $19.5 billion in 2021 to $35 billion in 2022. These fossil fuels accounted for more than 92% of Azerbaijan's exports and more than half of state budget revenue.

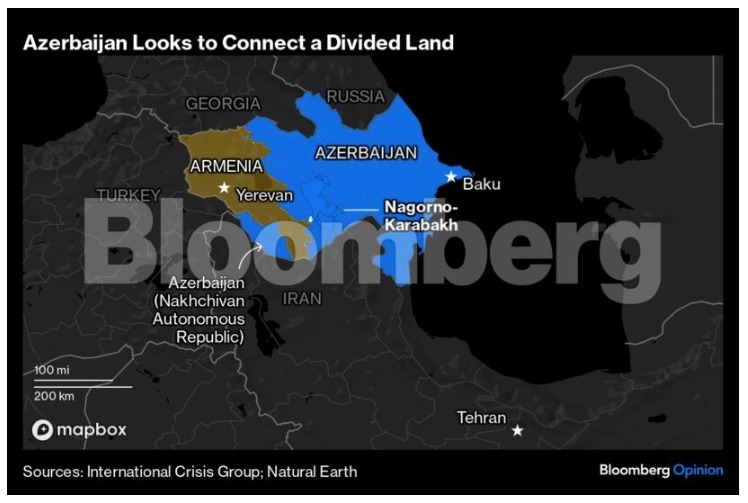

A detached Russia, a traditional security provider for Azerbaijan's local rival Armenia, also gave Aliyev leeway to seize the ethnically Armenian-controlled enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, ending 30 years of war and Azerbaijani humiliation with the very same brief and glorious military victory Putin sought to achieve in Ukraine.

The mass exodus of the Armenian population finally resolved the Karabakh issue and satisfied the desire of Azerbaijani public opinion for revenge – however unacceptable – after similar previous periods of ethnic cleansing against the Azeris in this enclave and its surrounding provinces. A triumphant Aliyev has called snap elections for next year to capitalize on patriotic euphoria, setting the stage for his third decade in power.

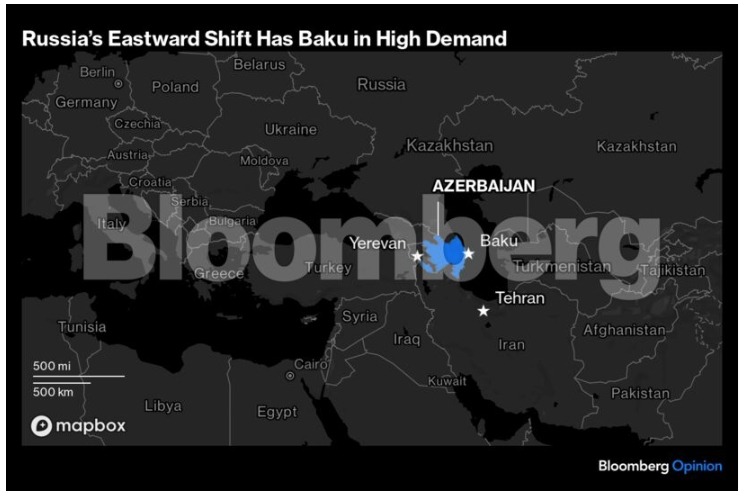

Everyone, it seems, now needs Aliyev. The EU not only wants its energy, but is also conscious that Azerbaijan controls the bloc's only viable route for access to Central Asian resources and energy markets that does not cross Russia or Iran, both hostile and sanctioned countries. The US, similarly, sees Azerbaijan's geopolitical value increase as Washington's relations with Moscow and Tehran deteriorate, despite doubts about ethnic cleansing in Karabakh. The same, for the reverse reason, are Russia and Iran.

"Sweet eyes" also from Moscow to Tehran

Moscow was once a staunch supporter of Azerbaijan's arch-rival Armenia, but that bilateral relationship has been shelved. Putin needs Azerbaijan's cooperation, as European sanctions force him to shift trade and energy routes eastward, while Russia's military ability to dictate developments in the Caucasus is in any case reduced at the moment due to meddling in other parts of the world.

Iran, long a neighbour that is politically close to Armenia, is also courting Baku. In October, Tehran proposed hosting a transit corridor linking Azerbaijan to Nakhchivan, an Azerbaijani province separated from the rest of the country by a strip of Armenian territory.

Improving cooperation with Baku has become more important for Iran since it agreed with Moscow earlier in May to establish a multibillion-dollar rail link through Azerbaijan, part of Russia's so-called North-South Transport Corridor, as the Kremlin seeks new, non-European markets.

From this already high base, things are expected to go even better for Aliyev. Azerbaijan has just locked in the right to host the next global climate change summit, COP-29. Obstacles to its effort have disappeared like ghosts in the fog in recent weeks, although Azerbaijan's meager human rights record and its position as another host with a large fossil fuel production may seem like drawbacks.

The protocol required the climate summit to head to an Eastern European country, and that pool shrank dramatically once Putin made clear he would veto any attempt by a government that supports Ukraine's war effort. Only Armenia, Azerbaijan and Bulgaria remained in the race, and Armenia withdrew on December 7 as part of an agreement under which the two sides agreed to exchange prisoners. A day later, Bulgaria, a potential beneficiary of the new gas transit flows between Azerbaijan and Europe, also resigned.

Self-confidence and repression

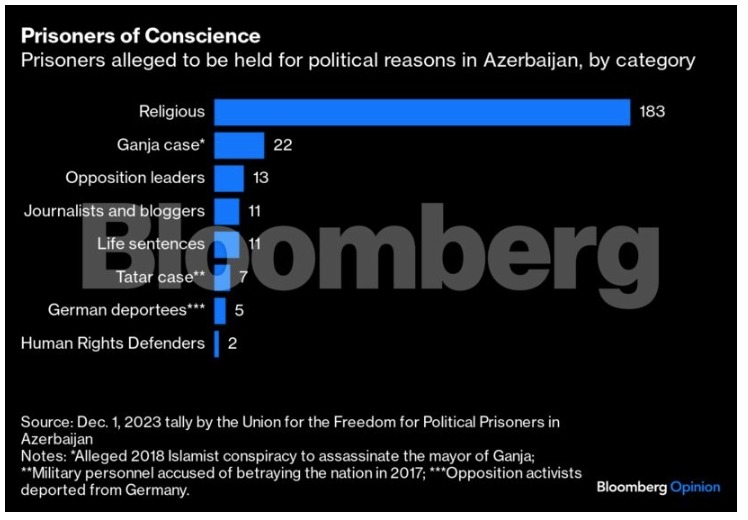

All this success and self-confidence should logically create a tendency for Aliyev to loosen control over a society that has been under increasing repression since his father, Heydar Aliyev, head of the Soviet-era KGB and former secretary of the CPSU in Azerbaijan, won the presidential election in 1993. Freedom House's latest report ranks the Caucasian country of 10 million people as "entrenched authoritarian regimes" and kleptocracies, scoring 1 out of 7 in the field of democracy.

Instead of reversing this trend, the government introduced a law last year requiring media outlets to subscribe to state ledgers and refusing to grant permission to those it didn't like. A list of political prisoners maintained by two Azerbaijani nonprofits, the Institute for Peace and Democracy and the Political Prisoner Monitoring Centre, counted 254 on December 1 – an increase of 19 from October, including journalists investigating regime corruption, and an increase of 99 from a year earlier.

Aliyev's combination of triumph and anger at criticism, particularly from the US, of Nagorno-Karabakh's ethnic cleansing makes it hard to imagine that he would buckle under international pressure at this time. However, its strength ultimately lies in Azerbaijan's value to European energy markets. His country is not interested in being left alone to confront its much larger Russian and Iranian neighbours in the long run, especially if Putin turns things in his favour in Ukraine. Aliyev is well aware that he needs to wean the economy off its over-reliance on energy to improve living standards and long-term growth prospects.

The fastest way to achieve this would be to secure aid and investment from Europe. Success would require major reform to break what the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has called "monopoly interests" in Azerbaijan, but it would also require more from Aliyev than imprison and silence any number of his critics.

Who knows, he might even win genuine, democratic elections. It's probably time to remind him.

Performance – Editing – Selection of Texts (2019-2023): G.D. Pavlopoulos