BBC News 13 July 2022 - by Ayeshea Perera

A state of emergency has been declared in Sri Lanka, and President Gotabaya Rajapaksa has fled the country.

His departure follows months of mass protests over soaring prices and a lack of food and fuel.

The country's foreign currency reserves have virtually run dry, and it has already missed debt interest payments.

What has been happening in Sri Lanka?

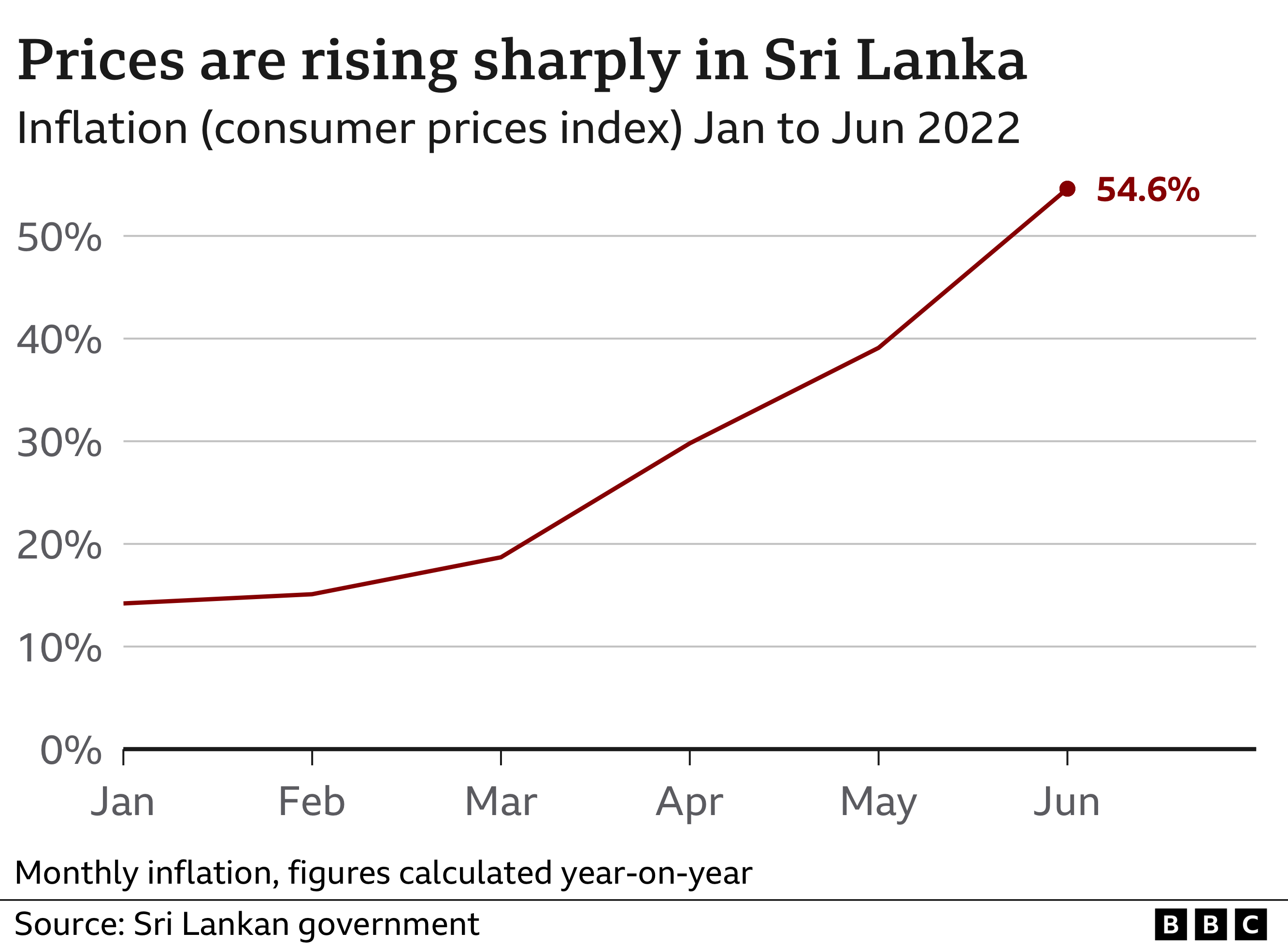

The price of everyday goods has risen sharply. Inflation is running at more than 50%.

There have also been widespread power cuts.

A lack of medicines has brought the health system to the verge of collapse.

The country doesn't have enough fuel for essential services like buses, trains and medical vehicles, and officials say it doesn't have enough foreign currency to import more.

This lack of fuel has caused petrol and diesel prices to rise dramatically since the start of the year.

In late June, the government banned the sale of petrol and diesel for non-essential vehicles for two weeks. It's thought to be the first country to do so since the 1970s. Sales of fuel remain severely restricted.

Schools have closed, and people have been asked to work from home to help conserve supplies.

What happens when a country runs out of money?

As well as not being able to buy goods it needs from abroad, in May Sri Lanka failed to make an interest payment on its foreign debt for the first time in its history.

The country had been given 30 days to come up with $78m (£63m) to cover the interest due, but central bank governor P Nandalal Weerasinghe said it could not pay.

Two of the world's biggest credit rating agencies also confirmed Sri Lanka had defaulted on its debt payments.

Failure to pay debt interest can damage a country's reputation with investors, making it harder for it to borrow the money it needs on international markets. This can further harm confidence in its currency and economy.

Is there a plan to solve the crisis?

President Rajapaksa has appointed Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe as acting president in his absence.

Mr Wickremesinghe has declared a state of emergency across the country and a curfew has been imposed in the western province while he tries to stabilise the situation.

Sri Lanka's government has more than $51bn (£39bn) in foreign debt, $6.5bn of which is owed to China, and the two countries are in negotiations about how to restructure the debt.

The G7 group of leading industrial countries - Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK and the US - had said it supports Sri Lanka's attempts to reduce its debt repayments.

The World Bank has agreed to lend Sri Lanka $600m, and India has offered at least $1.9bn.

The Sri Lankan government has also been in talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) about a possible $3bn (£2.5bn) loan.

The IMF - which works with its 190 member countries to stabilise the world economy - said the government would have to raise interest rates and taxes as a condition of any deal.

It would also require a stable government to be in place, so any bailout may be delayed until a new administration takes over.

Acting President Wickremesinghe had already said the government will print money to pay employees' salaries, but has warned this is likely to boost inflation and lead to further price hikes.

He also said state-owned Sri Lankan Airlines could be privatised.

The country has asked Russia and Qatar to supply it with oil at low prices to help reduce the cost of petrol.

What led to the economic crisis?

The government has blamed the Covid pandemic, which affected Sri Lanka's tourist trade - one of its biggest foreign currency earners.

It also says tourists were frightened off by a series of deadly bomb attacks in 2019.

However, many experts blame economic mismanagement.

At the end of its civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka chose to focus on providing goods to its domestic market, instead of trying to boost foreign trade.

This meant its income from exports to other countries remained low, while the bill for imports kept growing.

Sri Lanka now imports $3bn (£2.3bn) more than it exports every year, and that is why it has run out of foreign currency.

At the end of 2019, Sri Lanka had $7.6bn (£5.8bn) in foreign currency reserves, which have dropped to around $250m (£210m).

Former President Rajapaksa had also been criticised for big tax cuts he introduced in 2019, which lost the government income of more than $1.4bn (£1.13bn) a year.

When Sri Lanka's foreign currency shortages became a serious problem in early 2021, the government tried to limit them by banning imports of chemical fertiliser.

It told farmers to use locally sourced organic fertilisers instead.

This led to widespread crop failure. Sri Lanka had to supplement its food stocks from abroad, which made its foreign currency shortage even worse.