BBC News 17 April 2021 - by Kevin Connolly

|

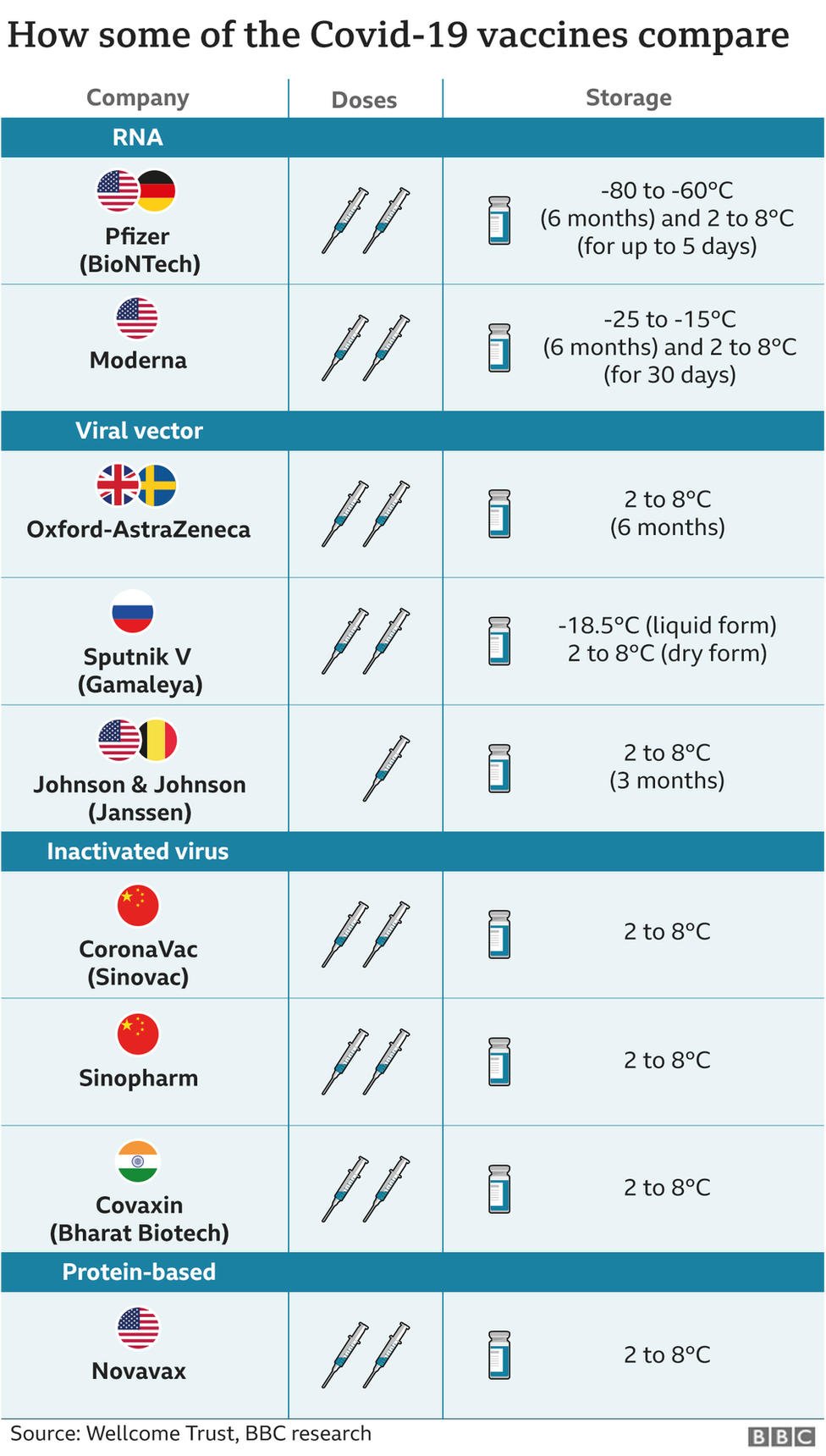

| Several European countries have shown interest in Sputnik although the EU's medicines agency is yet to approve it |

It's no coincidence that Russia has christened its Covid vaccine Sputnik V. The first time the world learned the meaning of the Russian word Sputnik was in 1957 when the Soviet Union launched the first man-made satellite into orbit.

At the height of the Cold War this startling evidence of Moscow's scientific and technical capabilities came as a huge shock to Western powers, which had assumed they enjoyed a comfortable technological lead over the Soviets.

That scepticism, though, has faded. Because once again Russian scientists have surprised the West.

A Russian 'tool of soft power'

An Eastern European diplomat, from a country that regards Russia as a clear and present threat, put it to me like this: "The search for vaccines in 2020 was rather similar to the race for space flight in the 1950s. Once again many outsiders have underestimated Russia. This is potentially the most powerful tool of soft power that Moscow has had in its hands for generations."

That word "potentially" is important here.

Sputnik V has not yet been approved by the EU's European Medicines Agency. But it's already been ordered by many different countries from Argentina and Mexico to Israel and the Philippines, and Russian officials say they have signed deals to produce it in South Korea and India.

There has been the odd hiccup in the rollout.

Argentinian President Alberto Fernández tested positive for Covid-19 in April after receiving two doses of Sputnik in January and February. That's a reminder that even if the Gamaleya Institute's claimed efficacy rate of 91.6% turns out to be true, a small statistical risk remains among those who've been vaccinated.

In Europe, though, the Sputnik vaccine has created problems that are more political than epidemiological.

The EU struggles to speak with a single, convincing voice on Russia.

That's partly a matter of history and geography. Lithuania and Poland are naturally more likely to consider Russia a threat than are, say, Portugal and Malta.

And there's also the perennial problem of balancing the EU's status as an importer of Russian gas with the EU's desire to punish Russia over issues like the attempted murder of leading opposition figure Alexei Navalny or the military build-up on the border of Ukraine.

Adding European reliance on Russia for vaccine supplies into that mix is going to make the relationship harder than ever to balance.

And yet Europe, or at least parts of Europe, are beginning to turn to Moscow out of frustration at the EU's painfully slow vaccine rollout.

'You have to think of your own interests'

Hungary has already bought and distributed considerable quantities of Sputnik V. France and Germany, among many others, are at least prepared to consider it, if and when the European Medicines Agency gives its approval. Hungary has used its right as an independent member state to grant emergency authorisation.

Veteran French diplomat Pierre Vimont, who's now a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe, says it's perfectly rational for member states to think about buying Sputnik.

"Even when you're facing an adversary," he told the BBC, "you have to think of your own interests."

Mr Vimont, as you'd expect of a man who's held some of his country's most important diplomatic postings, suggests that the European Union's attitude should be one of cautious pragmatism. That means acknowledging the excellence of Russian science but waiting for EMA authorisation as well.

He makes the point that countries using the jab on the basis of their own approval could face political difficulties with their own voters if things go wrong.

How Sputnik row brought down a prime minister

The case of Slovakia offers a salutary warning to others.

Its Prime Minister, Igor Makovic, secretly arranged to import 200,000 doses of the Russian vaccine. He was forced to leave his post late last month because he'd failed to consult his coalition partners.

Then Slovak scientists claimed the doses sent to Bratislava were different to samples of the vaccine sent elsewhere, prompting the Russians to denounce the claim as fake news and demand the return of the shipment. An offer from Hungary to approve the doses on Slovakia's behalf added a further layer of complexity.

Russia normally has to spend huge amounts of money on computer hacking and disinformation to spread discord and uncertainty in Europe. Now the vaccine appears to be achieving something similar without any effort.

Pierre Vimont of Carnegie says the Putin administration will be pleased. "I'm sure they are enjoying this," he said, "let's not be fooled. The use of vaccines by Russia and by China is a diplomatic instrument, a tool for soft power. Playing {EU} member states off against each other is naturally important to Russia."

A notable victory for Russia

There was a similar reaction from our Eastern European diplomat, who fears that European actions over cases like the poisoning of Alexei Navalny are generally too weak.

"What the vaccines episode shows," he told me, "is that we are quite capable of tying ourselves in knots over our dealings with Moscow without any help from the Russians."

There is a long way to run with all of this.

Russia still has a lot to do to increase production of its vaccine even as it boldly takes orders all over the world. This week it announced it was starting production of the drug in Serbia, the first European country outside Russia and Belarus.

It may also be planning to license production in Western Europe as well as India. But there's still the need for EMA authorisation: will the Russian data and the way it was collected meet EU standards?

But for now there is no doubt that Russia has scored a notable scientific and political victory.

The original Sputnik changed the world. Sputnik V may not represent an achievement on quite that scale but it is certainly helping to change the way Russia is perceived.