By Nicholas Karides

Never before have the media, that is the civically useful type that produce independent quality journalism, come under such relentless pressure and criticism. The gatekeepers, those tasked to speak truth to power, are increasingly being questioned by authorities and snubbed by the public whom they are meant to serve.

In the US, lauded until recently as the hub of absolute press freedom, an infantile but sinister president launches personal attacks on journalists and degrades the profession. In Hungary, an EU member state, the government intimidates and stifles media freedom while in Turkey, a once aspiring candidate state, the government just locks journalists up at will.

Populist leaders, their poisonous discourse and the unchecked new technologies that allow the spread of disinformation are shaking the people’s trust in the media and by consequence redefining the media landscape altogether. Yet, as Donald Trump and Viktor Orban ride the trend, it is useful to remember that the media have always been subject to political pressure and interference while their commercial viability has always been at the mercy of their owners’ whims or capitalism’s frequent breakdowns. Which is why the national contexts in which they operate have, rightfully, always come under scrutiny by independent monitors.

Their aim is to assess the quality of the media, the environment in which they operate and ultimately to help establish the quality that can command the public’s trust. Scrutiny of this constructive kind was released last week by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom of the European University Institute in Florence. The Media Pluralism Monitor 2020, co-funded by the European Union, examined the health of media ecosystems in EU member states, including a now departed member state, the UK, as well as in Albania and Turkey.

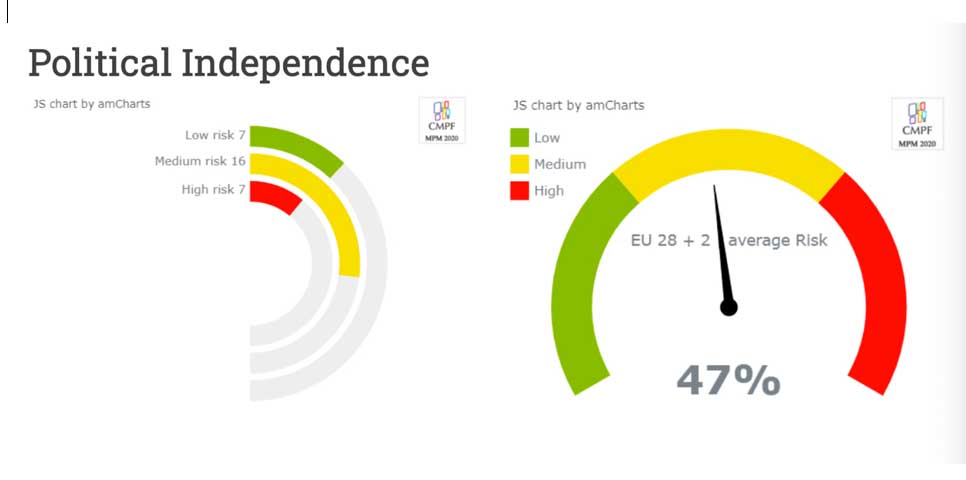

Four key risk areas were assessed: Basic Protection, i.e. rights and access to information, the working conditions of journalists and the effectiveness of media authorities; Market Plurality which assesses the legal and economic environment, transparency of ownership, media concentration, viability, and owner influence on editorial content; Political Independence, i.e. the autonomy of the newsroom, political control and influence, election coverage, advertising, regulations and funding, and, last, Social Inclusiveness which examines the degree of media access for minorities, women and people with disabilities as well as the overall level of media literacy and protection against hate speech.

The MPM2020 found that Basic Protection remains strong overall with the majority of the countries considered low risk and only one, Turkey, seen as high risk. However, when it came to Market Plurality, risks of commercial and owner influence over editorial content have risen with only five countries deemed low risk (Denmark, France, Germany, Portugal and the Netherlands) with 11 at medium risk (Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Spain and the UK) and the remaining 14 at high risk.

Serious concerns also emerged on Political Independence with Malta, Hungary and Poland along with Bulgaria, Romania, Slovenia and Turkey found to be high risk. Only Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Sweden were low risk; the majority, including Cyprus, fell within the medium risk range.

As disinformation eats away at objective reporting, media literacy, the capacity to understand what is fake or biased, has become a key factor. Only six countries were found to have comprehensive media literacy policies. Five, Albania, Croatia, Hungary, Romania and Cyprus have no media literacy policy at all.

Cyprus’ risk level

In terms of Basic Protection, constitutional and legal provisions continue to offer citizens safeguards and effective protection of their rights connected to freedom of expression but there are areas of concern such as digital underdevelopment while the right to access to information still requires legal recognition.

The situation is poorer on Market Plurality. The law does ensure transparency in media ownership and avoidance of cross media concentrations but only in broadcasting. An outdated and deficient press law and the absence of a digital media legal framework as well as the increased corporate influence and pressures on journalists’ employment conditions are problems, heightened by lack of reliable data.

Editorial independence in Cyprus is in principle warranted by both regulatory and self-regulatory provisions. However, the rules make very limited provisions on the effective protection of journalists and the avoidance of political interference into their work. The key issue remains the pursuit of the political agendas of media owners, sometimes without any visible interference and often led by corporate rather than actual political aims. This enforces a degree of self-censorship and compliance among editorial staff.

Crucially, a subculture of informal relations exists between the political class and media owners and journalists which more than any other factor affects focus, topic selection and nuancing. There are also recurring problems with the governance and funding of Cyprus’ public service media, CyBC, and the influence the government and political parties retain over it.

Where Cyprus fares badly is Social Inclusiveness. Access to the media is mostly reserved for mainstream groups with minorities, women and other social actors sidelined despite evolving plurality and multiculturalism. Much needed media literacy actions are limited and lack policy direction despite valiant efforts by academics and other stakeholders.

And though media literacy may be seen as the least important in terms of immediate impact and a country’s overall image, it is potentially the most significant in terms of achieving better across-the-board results in the future. A well-informed media-literate populace is more likely to demand Market Plurality and not likely to tolerate Political Interference.

Trumpism and Orbanism are the result of complex factors. Media literacy would certainly not have prevented them. But it can be argued that for a confused public caught between populist politics, fragile economics and a hounded media it might make just enough of a difference to avert total disaster in the future.

Nicholas Karides was one of the Cyprus experts for Media Pluralism Monitor 2020 along with team leader Christoforos Christoforou. Individual country reports can be accessed at https://cmpf.eui.eu/mpm2020-results/

@NicholasKarides