in-cyprus 17 June 2020 -Bouli Hadjioannou

Coronavirus is able to pass between two people standing up to one metre apart even if one of them is wearing a surgical grade face mask, the Daily Mail reports, citing a study by researchers from the University of Nicosia published in the journal Physics of Fluids.

They also found that masks became even less efficient when people repeatedly cough into them.

Co-author Professor Dimitris Drikakis of the University of Nicosia said a mask alone cannot prevent the transport of saliva droplets completely.

“Many droplets penetrate the mask shield and some saliva droplet disease-carrier particles can travel more than 1.2 metres,” he said – although most travel under 1 metre.

Face masks are believed to slow the spread of the pandemic but little is known about how well they work or under what conditions they won’t work.

The study found face masks can reduce transmission of airborne droplets – but not eliminate them completely.

Without a mask these droplets travel twice as far – so wearing one will help in reducing the risk of passing on the disease.

However, repeated coughing, a symptom of coronavirus, reduces the efficiency of a mask and so more droplets are let through.

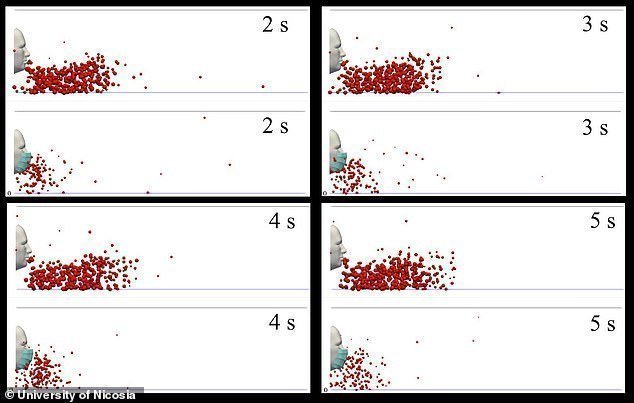

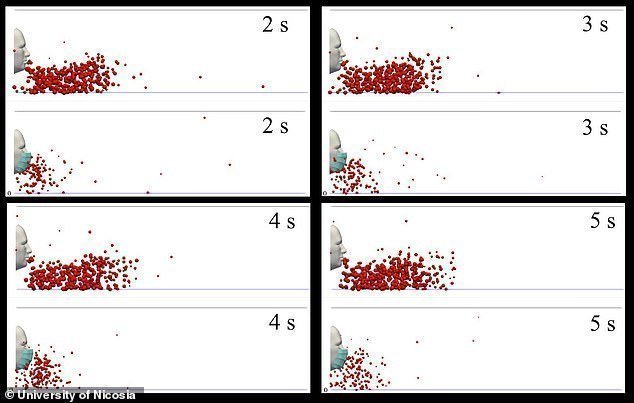

Previous work by the same team showed droplets of saliva can travel 6 metres in five seconds when an unmasked person coughs.

This time they used a precise computer model to map out their expected flow patterns when a mask-wearing person coughs.

They took into account potential weather conditions, air turbulence and even the skin and mouth temperature of the person coughing.

The researchers performed numerical simulations that account for droplet interactions with the porous filter in a surgical mask.

“The results are alarming. Even when a mask is worn, some droplets can travel a considerable distance during periods of mild coughing,” the authors wrote.

The tests were based on a standard surgical mask exhibiting initial efficiency of about 91% when preventing droplets from escaping.

For visualisation purposes, the droplets were scaled up by a factor of 600 compared to their actual size – making them easier to track.

“The droplet sizes change and fluctuate continuously during cough cycles as a result of several interactions with the mask and face,” said Drikakis.

Co-author Dr Talib Dbouk said masks decrease the droplet accumulation during repeated cough cycles – effectively they get worse at stopping droplets escaping.

‘”However, it remains unclear whether large droplets or small ones are more infectious,” the co-author said.

They advised health care workers to wear much more complete PPE (personal protective equipment) when caring for a patient.

This should including helmets with built-in air filters, face shields, disposable gowns and double sets of gloves – changed regularly.

The researchers also urged manufacturers and regulatory authorities to consider new criteria for assessing mask performance that account for flow physics and cough dynamics.

Their earlier study published in the same journal in May found keeping 2 metres apart may not be enough to protect against coronavirus.

Droplets carrying the potentially deadly bug can travel 6 metres in five seconds – even in the slightest of breezes.